Japanese Princess Yuriko, oldest member of imperial family, dies at 101

Biden fiercely embraces the non-swing state of South Carolina

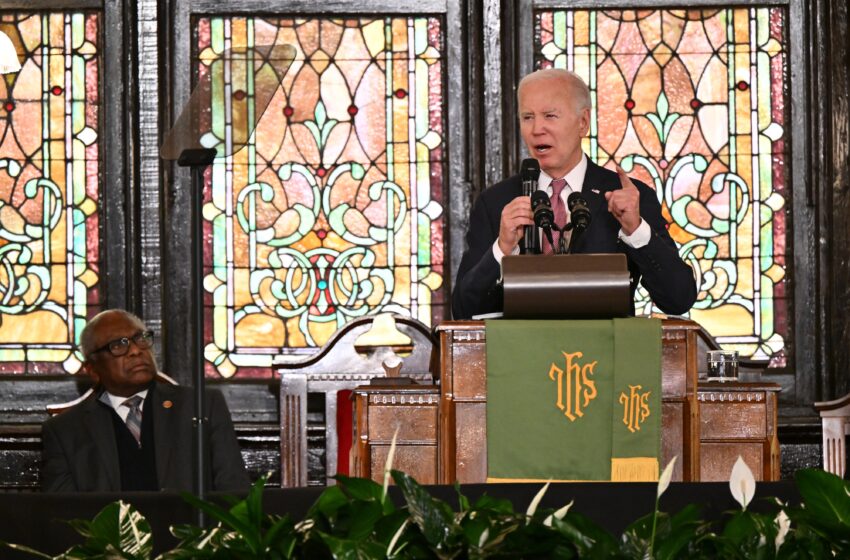

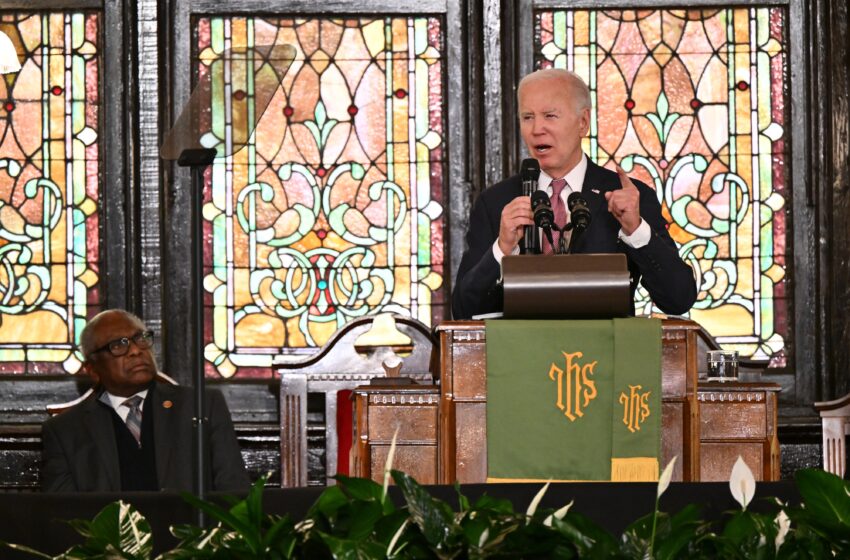

RICHLAND, S.C. — On two weekends in January, President Biden turned up at churches in South Carolina, telling parishioners about the racism and hatred he ran for office to combat, then detailing the progress Black Americans have made since then.

Vice President Harris visited this state, too, speaking at a Martin Luther King Jr. Day celebration to criticize efforts “to erase, overlook, and rewrite the ugly parts of our past.” First lady Jill Biden addressed South Carolina teachers last week, urging them to support her husband.

And Rep. James E. Clyburn (D-S.C.), one of the co-chairs of Biden’s reelection campaign, said he had to apologize to organizers of a Democratic Party gala recently for going overtime in enumerating everything Biden has done for Black voters.

There is little mystery about how Biden will fare in Saturday’s South Carolina Democratic primary, where the sitting president is expected to easily capture his party’s first official 2024 contest. The outcome in November is not a nail-biter, either: South Carolina’s electoral votes have gone reliably red for half a century, including 2020, when Trump won the state by nearly 12 percentage points.

It is unusual for a president seeking reelection to lavish time and energy on a state that is not remotely up for grabs. But Biden seems to view South Carolina as a stage for sending a message to skeptical Black voters more broadly.

“We have the lowest Black unemployment rate recorded in a long, long time,” Biden said at Emanuel A.M.E. Zion church in Charleston, interspersing economic tidbits with soaring calls for racial equity. “More Black Americans have health insurance than ever, bringing peace of mind and dignity to their lives.”

Clyburn, one of the senior Black officials in America, argued that Biden has a strong case. “On substance, there hasn’t been a Democratic president that has done as much for Black Americans in this country since Lyndon Johnson,” he said in an interview.

Yet polls suggest some Black Americans are disappointed with Biden’s record. A Pew Research Center poll in January found that 48 percent of Blacks nationally approved of Biden, and 49 percent disapproved. That was down from January 2023, when 60 percent of Black Americans approved and 35 percent disapproved.

The Biden team sees South Carolina, which rescued Biden’s teetering candidacy four years ago, as an opportunity to shore up and re-energize a loyal constituency.

Operatives on both sides foresee a tight potential general election matchup between Biden and former president Donald Trump, the leading GOP contender. Biden’s speeches are routinely interrupted by demonstrators unhappy with his handling of the conflict in the Middle East. And even supporters worry that the electorate has not connected improvements in their lives with Biden’s policies.

Clyburn conceded that Black voters are not overly excited about Biden, but he blamed Republicans. “The enthusiasm is not there because [Republicans] are working full time tamping down enthusiasm, misrepresenting what’s out there,” Clyburn said. “We know the misinformation is out there. We know where it’s coming from. And those of us who know need to make other people understand.”

In visit after visit to South Carolina, Biden, Harris and a small army of campaign surrogates have highlighted the benefits the administration has brought to Black voters, who are central to the president’s coalition.

At Emanuel A.M.E. Zion last month, Biden stressed that the same sort of grievance that led a man to kill nine members of that congregation in 2015 motivated a pro-Trump mob to storm the U.S. Capitol in 2020.

In Richland, Biden campaign co-chair Mitch Landrieu noted that the president had worked to cap the price of insulin at $35 a month to control diabetes, a disease that afflicts Black people at disproportionately higher rates. In the state’s capital on Martin Luther King Jr. Day, Harris spoke of Republicans who “attack the sacred freedom to vote.”

Biden and his allies regularly remind Black voters in South Carolina that their ballots on Saturday will affect how other people view Biden across the country — just like four years ago.

“It’s because of this congregation and the Black community of South Carolina — not exaggeration — and Jim Clyburn that I stand here today as your president,” Biden said at the Emanuel church. “Because of all of you. That’s a fact. That’s a fact. And I owe you.”

In 2020, Biden had taken fourth place in the Iowa caucuses, calling it a “gut punch.” He did even worse in New Hampshire, and on the night of the Granite State’s primary, he instead dashed to South Carolina, telling voters in a fiery speech that the preferences of Black Americans had not yet been heard.

Eighteen days later, Biden won South Carolina’s primary in commanding fashion, catapulting him to a slew of Super Tuesday victories and, ultimately, the Democratic presidential nomination.

In the general election, Black voters helped Biden land victories in swing states such as Georgia. The nation faced a racial reckoning in 2020 after the killing of George Floyd by Minneapolis police, and Biden and the Democrats made equity a central plank of their platform, pledging to fight for voting rights, police reform and, more broadly, an end to systemic inequality.

But many of those initiatives have been stymied in Congress. In 2022, Biden signed an executive order on police reform that fell short of the more sweeping legislation he’d hoped for.

In many ways, Biden has spent the past three years repaying South Carolina for its pivotal role in sending him to the White House. He put his weight behind making the South Carolina primary first in the nation, saying its population represents the party’s diversity far more than Iowa’s or New Hampshire’s.

Political analysts give several reasons for the declining enthusiasm for Biden among Black voters: Many of the race-related promises that Democrats campaigned on in 2020 have not come to pass. They did not have enough votes to codify voting rights protections into law. Efforts at police and criminal justice reform fizzled as Republicans accused Democrats of being soft on crime.

Others cite a lack of information about the advances Black people have made under Biden, including the appointment of Black officials to numerous high-profile positions as well as the brick-and-mortar projects that have come to Black neighborhoods.

“What Biden and Democrats have been delivering is tangible. You can feel it. You can touch it. You might be able to hear it if you ride down the interstate,” said Christale Spain, chair of the South Carolina Democratic Party. “So it does excite people when they realize ‘Oh, that was Biden. This did happen because of Biden.’”

Spain said the Biden campaign’s effort to talk about searing racial struggles in this Southern state has been especially potent.

An estimated 80 percent of African Americans can trace their ancestry through the Port of Charleston. The state was the first to secede from the United States during the Civil War, and the Confederate Flag flew over the statehouse until 2015. Emanuel A.M.E. Zion, where Biden spoke on Jan. 7, was the site of a mass shooting of church parishioners by a man who said he hoped to ignite a race war.

Biden and his surrogates have tried to stress his administration’s high-profile achievements: He ushered in the first Black woman as vice president and the first Black woman to be a Supreme Court Justice. He has appointed more Black women to the federal bench than all other presidents combined.

At the same time, the president’s team has sought to highlight economic benefits baked into the larger bills that Biden has pushed through Congress.

Clyburn said many people assume that because Biden isn’t full of fiery venom on the campaign trail, he must not be fighting hard for Black Americans.

“You ask them a question, ‘What’s your problem with Joe Biden?’ and they immediately start talking about his style — ‘He doesn’t seem like he’s fighting for us,’” Clyburn said. “For some people, you’ve got to be yelling. You’ve got to be calling people names to show that you’re fighting. You can fight a pretty good battle with a pen and a piece of paper.”

But some party insiders say the enthusiasm problems run deeper than messaging.

Black voters often have a hard time squaring what Biden supporters tout as one of the most successful presidencies in history with what they see as a dearth of progress on issues like voting rights, and sometimes with a lack of visible changes in their communities, they say.

“In South Carolina, the negative statistics are still off the charts,” said one South Carolina Democratic strategist, who asked not to be named for fear of sullying relationships. “You name it: infant mortality, and diabetes, and we’re still 43rd in education. Black people are bearing the brunt of the worst of what Republican domination has done to South Carolina. But we are expected now to be the reason why Biden is running again.”

Fletcher Smith, a former state representative who was a Biden surrogate in the 2020 primary, said he is worried that Biden is leaning too heavily on symbolism and lofty words, rather than the specifics of what he has brought to the community.

The president’s signature achievements, from an infrastructure law to a climate package, were designed in part to put resources into Black communities, his supporters say, but that is not always recognized.

“Symbolism can get you only so far. We want to know what you’re going to do,” Smith said. “How many Blacks were actually standing up there saying they’re going to make some money with the infrastructure bill? If you don’t have Black folks out there with some shovels, saying, ‘We’re going to make some money, too,’ it’s not enough.”

He added, “It’s one thing to go down there and talk about God and an equal piece of the pie and all that. But we want to see real results.”