North Korea to mass produce self-detonating explosive drones, state media reports

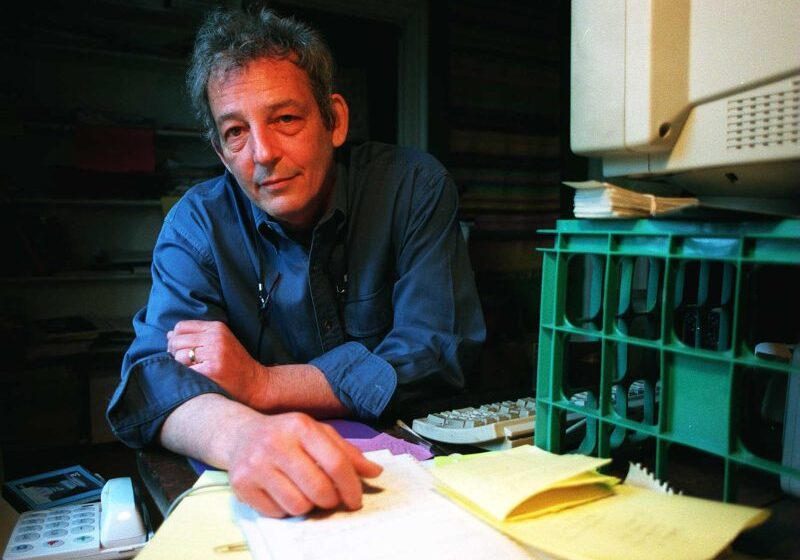

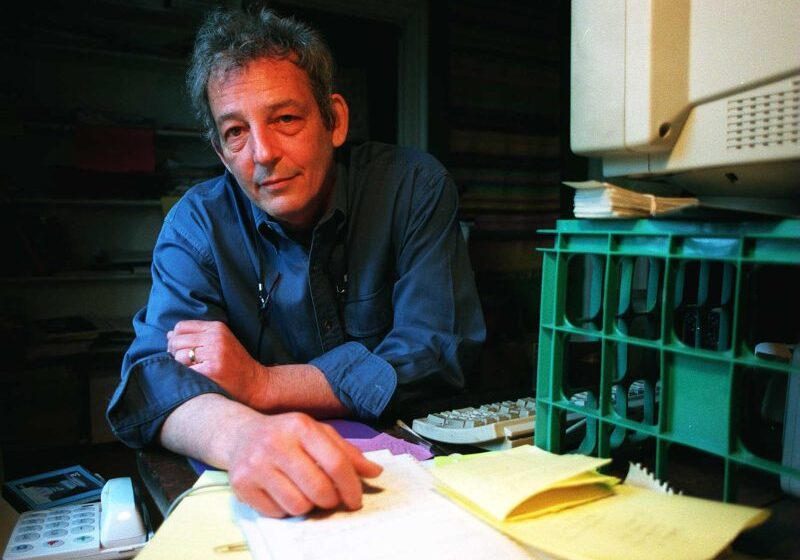

Ross Gelbspan, author who probed roots of climate change denial, dies at 84

Ross Gelbspan, a journalist and author who followed the money trail of climate change denial, exposing how the energy industry and lobbyists pushed narratives to counter overwhelming evidence that use of fossil fuels was driving global warming, died Jan. 27 at his home in Boston. He was 84.

The death was announced by his family. Mr. Gelbspan had chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Mr. Gelbspan’s coverage for the Village Voice, Boston Globe and others touched on the emerging research linking greenhouse gas emissions to rising temperatures and consequences such as melting ice caps and the potential for more powerful storms. He began to dig into the network of climate change denial after being peppered by their backers.

A year after leaving daily journalism, he planned to pursue a project based on a 1995 essay in The Washington Post that drew connections between a warming planet and the greater potential for the spread of diseases. He then received a flood of responses, including many that claimed he was misled about climate change, he recalled.

Mr. Gelbspan feared he was on the wrong track and considered dropping the book project. He followed through, however, with interviews he had already scheduled with leading climate scientists, who gave him compelling data on warming and details about the campaign to discredit the findings.

“I was a journalist, not an environmentalist,” he said last year in a memoir-style presentation posted on YouTube. “I didn’t get into the climate issue because I love the trees. I tolerate the trees. I got into the issue because I learned the coal industry was paying a handful of scientists under the table to say nothing was happening to the climate.”

He also took aim at his own profession, arguing that journalists needed more aggressive standards on climate coverage to filter out industry-funded groups downplaying the threats. The traditional model of journalistic balance, he said, was doing a disservice by giving a forum for claims that sowed doubts about realities.

“The science is very clear on one point: Climate stabilization requires that humanity cut its consumption of carbon fuels by about 70 percent,” he said. “That made the motivation behind the disinformation campaign … very clear.”

As climate change increasing became a political dividing line, often with Republicans embracing views that question the causes and pace of a warming planet, Mr. Gelbspan amplified his stance. He described the efforts to devalue the science on climate change as similar to earlier attempts by tobacco companies to cloud the medical reports linking smoking to cancer.

“It is an excruciating experience,” he wrote in his book “The Heat Is On” (1997), “to watch the planet fall apart piece by piece in the face of pathological denial.” He described political leaders and companies that pushed climate change skepticism as “criminals against humanity.”

He acknowledged the power of the global marketplace. More than two decades ago, he noted early moves by oil giants such as BP and Shell to invest in renewable energy projects as well as plans by automakers to expand production of hybrid and electric cars. At the same time, he decried the pressures from energy companies on many political leaders to keep regulations from squeezing too hard.

ExxonMobil publicly pledged to halt its funding of scientists and groups that pushed to undercut climate change threats, but still privately sought to undermine climate science, according to documents disclosed last year by the Wall Street Journal. In “The Heat Is On,” Mr. Gelbspan cited a 1991 memo from an energy lobby that encouraged the spread of selected data and talking points to “reposition global warming as theory rather than fact.”

Other countries with major carbon footprints, including China and India, also have faced international criticism for not making significant cuts in emissions. In Mr. Gelbspan’s view, the United States holds additional blame for sending inconsistent messages on climate policy, such as President Donald Trump withdrawing in 2017 from the Paris agreement on goals to battle climate change that was supported by the Obama administration.

“There are few people in this country who have done more than Ross Gelbspan to make sure that the problem of global warming gets the attention it deserves,” wrote Rob Sargent, who was a senior energy analyst for the Association of State Public Interest Groups based in Boston.

Mr. Gelbspan’s 2004 book, “Boiling Point,” delivered a harsh assessment of general coverage of climate issues, criticizing journalists for repeating the “manufactured denial” of the energy companies and paid representatives.

Mr. Gelbspan said he remained a strong advocate of traditional journalistic practices of balance and multiple viewpoints. With global warming, however, he said journalists had a responsibility to learn the subject and keep out misleading information and ideas.

“The news media are reflecting the cowardice of the larger society in not looking reality in the eye and reporting the truth of our situation,” Mr. Gelbspan told the Columbia Journalism Review. “It is a damning betrayal of the public trust.”

Former vice president Al Gore — who raised alarms about global warming in the 2006 documentary “An Inconvenient Truth” — called Mr. Gelbspan a journalist who “now feels called to a kind of mission.”

In Gore’s review of “Boiling Point” in the New York Times, he applauded Mr. Gelbspan for highlighting the “specific failures and misdeeds” of politicians, energy companies and journalists on climate issues and then proposing “bold solutions that — unlike more timid blueprints already on the public agenda — would in his view actually solve the problem.”

Ross Gelbspan was born June 1, 1939, in Chicago. His father ran a kitchen supply company, and his mother was a homemaker.

Mr. Gelbspan graduated from Kenyon College in Gambier, Ohio, in 1960 with a degree in political philosophy. He worked as a reporter and editor at the Philadelphia Bulletin and The Post in the 1960s before joining the Village Voice.

His assignments for the Voice included three weeks in the Soviet Union in 1971 that involved interviews with political dissidents. He was interrogated for six hours by the KGB before he was allowed to leave Moscow. Parts of his four-part series were reprinted in the Congressional Record.

In 1972, he did some of his first stories on ecological issues while covering the U.N. Conference on the Human Environment in Stockholm.

He joined the Boston Globe in 1979 and, as special projects editor, oversaw a series examining discrimination against Black job seekers and workers in the Boston area. The series won a 1984 Pulitzer Prize for investigative reporting. Mr. Gelbspan’s work on climate issues at the Globe included stories that coincided with the U.N. Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro in 1992.

“The Heat Is On” received national attention when President Bill Clinton said he was reading it. Mr. Gelbspan’s previous book, “Break-ins, Death Threats and the FBI” (1991), examined harassment and surveillance of domestic opponents of Reagan administration policies in Central America.

He married the former Anne Charlotte Broström in 1973, a year after they met at the U.N. environmental conference in her native Sweden. She worked building housing for previously homeless families in eastern Massachusetts. Other survivors include two daughters and a sister.

In an interview with Mother Jones magazine in 2005, Mr. Glebspan described how questions about climate change had moved rapidly from academic and scientific circles to become part of the vernacular.

“They know something is wrong even if they don’t understand greenhouse gases,” he said. “They sense something is changing and that makes people instinctively uncomfortable, and that makes them much more receptive to looking at the causes.”