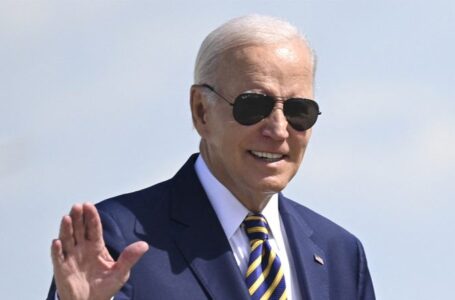

Majority say Biden will be remembered poorly as president says farewell to the nation: poll

GOP House hard-liners won’t compromise. They’re losing key fights because of it.

Speaker Mike Johnson (R-La.) believes there is a simple answer to the question of why House Democrats are more effective at working together than members of his conference: Republicans are just too principled.

Democrats, Johnson told conservative radio host Hugh Hewitt last week, “move in a herd” and “act like a union” following their leader because there’s no diversity of opinion causing them to stray — their groupthink could even be described as the behavior of “socialists.” Republicans, however, can’t be forced to unite because they’re “rugged individualists.”

“We’re deeply principled and philosophical and it’s difficult to get us to move in tandem sometimes,” Johnson said. “That’s a blessing. I love that part — except when you have a one-vote margin.”

That’s one way of putting it. What Johnson didn’t articulate was how a rowdy bunch of flamethrowers on his right flank — roughly 15 members, many members of the vocal Freedom Caucus — has pretty much sabotaged any hope of a conservative legislative agenda this Congress. These hard-liners have refused to compromise on everything from immigration reform, to government spending to foreign aid for Ukraine, and in the process have yielded power to a bipartisan coalition of lawmakers.

Rep. Blake D. Moore (R-Utah), who serves as the GOP conference vice chair, said Republicans would get more conservative wins landing on the president’s desk if they weren’t so self-defeating.

“That’s the part I wish every American can get. That by pretending to be super conservative, by taking down a rule and fighting the establishment … the outcome is, you have less conservative legislation. So that’s okay for you individually. It’s not better for the country,” he said, referring to a procedural tactic governing floor debate known as a rule.

This stubborn adherence to ideological purity is causing the hard-liners to lose leverage in a House where the GOP has just a two-vote majority. Their intransigence means that Johnson — though he risks his job by doing so — has continued to turn to Democrats to pass high-priority legislation to keep the government funded and send foreign aid to U.S. allies such as Ukraine and Israel.

When Republicans return to Washington on Monday, they will continue to struggle to pass anything without Democratic help. Their inability to agree has made them appear publicly and privately chaotic, misunderstood and afraid they will lose the majority in November. It has led to some privately calling for more time at home in their districts, knowing little will probably get done the rest of the year.

“My recommendation is we stop trying to bend the policy for the year because there’s really nothing we can do with this majority right now,” one swing-district Republican lawmaker said. “So now the focus is on us keeping the majority and figuring our s— out internally as a family because we may keep the majority, but it may only still be by one to four seats. So we’re going to have this problem.”

No one has been more vehemently opposed to Johnson’s strategy than Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene (R-Ga.). The MAGA firebrand, along with Reps. Thomas Massie (R-Ky.) and Paul A. Gosar (R-Ariz.), continues to support the speaker’s ouster through what’s known as a motion to vacate. Others, such as freshman Rep. Elijah Crane (R-Ariz.), remain open to the idea of removing Johnson.

“At the end of the day, this is so much bigger than me, or a motion to vacate or Speaker Mike Johnson,” Crane said about his disillusion with the emerging House governing coalition. “To me this comes down to, are we going to try and save this country or are we just going to continue on with the Washington uniparty that continually sells out the American people?”

Johnson’s foes failed to bring the motion to oust him before the House adjourned a week ago, with Greene arguing she wanted her colleagues to feel the outrage from their constituents. Greene tried to drum up criticism by asking followers on social media whether they “support Mike Johnson for Speaker,” and Massie characterized Johnson’s reliance on Democrats as “unforgivable”

Given the threat looming over Johnson and their inability to compromise, Republicans will probably resort to passing noncontroversial legislation that doesn’t rankle their conference, while also prioritizing possibly cutting federal funds to universities and piecing together an “election integrity” bill Johnson and former president Donald Trump floated earlier this month. (Voting by undocumented migrants is already illegal in the United States.)

But Congress must reauthorize the Federal Aviation Administration by May 11 and fund the government for the 2025 fiscal year while reauthorizing a farm bill by Sept. 30. Given how the far right’s unrealistic demands to curtail spending plagued the last spending process, it’s unlikely Republicans notch aggressively conservative wins this time around.

Some more pragmatic Republicans argue their colleagues need to accept the reality and work under the confines of their slim majority, and a Democratic-controlled Senate and White House.

“I get to serve with a lot of great people. I’m a little surprised with how naive people are being right now. I mean, the reality is the Democrats are in control of the Senate, the Republicans in control of the House,” said Rep. Dusty Johnson (R-S.D.), who chairs the conservative but governing-focused Main Street Caucus. “So anything that we were ever going to get done was going to be a work product that was going to require good people on both sides.”

Hard-liners see it much differently.

They argue it’s their colleagues’ willingness to compromise that will end with them in the minority. Republicans should use the reins of the majority more forcefully, they say, to aggressively incorporate “America First” promises to voters on the campaign trail, echoing Trump, the presumptive 2024 presidential nominee. Those promises include significantly curtailing spending and clamping down on migrants at the southern border. They prefer to protest, shut down the government and risk the GOP majority if Washington isn’t entirely overhauled.

“Here we go again, we’re negotiating with the Senate and the Democrats to what will seamlessly continue this slide down into the abyss of greater fiscal crisis and ‘America last’ policies,” championed by President Biden and congressional Democratic leaders, said Freedom Caucus Chair Rep. Bob Good (R-Va.).

Stuck in the middle is Johnson, who has endlessly sought to appease all corners. Plucked from obscurity and chosen to lead the House six months ago because he had no enemies, the speaker has now rankled everyone. The far right accuses Johnson of stripping his ultraconservative credentials to embrace bipartisan policies, while the governing coalition is frustrated its taken the speaker too long to realize the hard-liners can never be won over.

Rep. Juan Ciscomani (Ariz.), a swing-district Republican who also belongs to the Main Street Caucus, echoed many governing colleagues who argue their first priority, “as a Republican conference is to pass legislation with Republican support.”

“When that doesn’t happen,” he said, “Then the option is to either give up and walk away or look for a way to not get the full win that we were hoping for, but get a win. … And that’s when it makes sense to partner with Democrats.”

Johnson has tried to incorporate the far right into discussions, but the group has often repelled his asks. When Republicans went to the Texas-Mexico border earlier this year, members of the Freedom Caucus rented their own bus so as not to mingle with the larger group.

And more recently when Johnson asked members to get briefed ahead of voting to reauthorize a section of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act, those hard-liners held their own separate briefing, according to multiple Republicans familiar with the events, who like others interviewed for this story, spoke on the condition of anonymity to discuss private happenings.

Members of the far right consider Johnson a weak speaker, viewing him as having been steamrolled by Democrats rather than accepting incremental conservative wins. They would prefer moving ultraconservative legislation with no chance of passing the Senate or being signed into law, and recessing the House no matter the consequences such as a potential government shutdown.

“I’ve told the speaker to his face, and I say it again, the American people, they’re watching what we do. And they know something, if you surrender, you lose every time,” Rep. Andy Biggs (R-Ariz.) said before 101 Republicans and 185 Democrats passed the government funding bill in March. “But doggone it, fight! This is capitulation. This is surrender.”

Johnson and Republican appropriators negotiated the spending deal, but they were stuck following parameters agreed to by Biden and then-Speaker Kevin McCarthy (R-Calif.) when they agreed last year to raise the debt ceiling by capping spending for two years at roughly $1.7 trillion.

Eleven far-right Republicans revolted against that deal by breaking a two-decade tradition that the majority allows floor debate even though lawmakers might oppose final passage. To end the blockade, McCarthy directed the House Appropriations Committee to cut $3 billion from the spending agreement, which resulted in difficult votes for vulnerable Republicans.

But McCarthy and hard-liners could never agree once the spending bills got to the floor and even rejected including a conservative border security bill, known as H.R. 2, days before the government was set to shut down. Left with few options, McCarthy chose to work with Democrats and keep the government open using a process known as suspension of the rules, which requires a two-thirds majority. He became the first speaker removed from office three days later.

Johnson has had to consistently rely on the same tactic.

Earlier this year, members of the Freedom Caucus were pushing Johnson to pass a short-term government funding bill that included their border security bill, the exact proposal they rejected months earlier.

Good acknowledged he was “against” the agreement “then, but now we’re at a different position. You recalibrate sometimes. You fight the battle you’re in, not the battle you wish you were in.”

Far-right Republicans have since voted against Johnson’s spending package, joined with far-left liberals to obstruct a spy agency surveillance reauthorization, and joined a majority of conservatives in opposing Ukraine aid, all while admonishing their GOP colleagues who backed all the measures as traitors to the base.

Over the past year, far-right members have blocked debate seven times on the House floor.

Most recently three hard-liners went a step further and blocked consideration of a border security bill that largely included H.R. 2 from even reaching the House floor to protest Johnson’s Ukraine strategy. The border bill could have passed the House by a simple majority, but the blockade forced Johnson to require a two-thirds majority. It failed.

So far, there have been no repercussions for Republicans who defy leadership and it doesn’t sound like any are coming soon. Some would like to see the obstructionist Republicans removed from the Rules Committee, for instance.

In the Hewitt interview, Johnson acknowledged it’s “a very delicate balance” in a slim majority to make such decisions because “there are reactions and reverberations from the actions.”

“If I start taking people off committees right now, it’s likely that I cause more problems than I solve,” he said in a statement that made clear the confines in which the conference must work under until the next election.

Pragmatic Republicans believe that far-right colleagues oppose legislation out of fear of Trump’s powerful and influential base. During a meeting last year between the chairs of the House GOP’s five ideological families, Rep. Scott Perry (R-Pa.) admitted as much, according to four people present: that it was easier for some far-right members to vote against bills to avoid the backlash at home. Meanwhile, far-right members believe the governing coalition also votes out of fear of not being reelected.

“There’s always a reason: the majority is too thin, ‘Oh I’d be there with you if I could wave my magic wand, we’ve got elections this year.’ … There is always an excuse for Republicans to fail,” Rep. Chip Roy (R-Tex.) said at a news conference last month, referring to colleagues who don’t want to push a forceful conservative agenda. “They’re the ones running in fear rather than leading.”

Both the hard-liners and the governing wing want Republicans to grow their majority — but with members like themselves. It’s why the fight has spilled onto the campaign trail as Republicans stump against their own colleagues.

“You got to get people that are willing to cut spending and address the border, and you got to have the courage to do it,” said Rep. Ralph Norman (R-S.C.), who has endorsed a challenger running against a colleague in the South Carolina delegation. “I’d say the rationale for why we [fight] is if you don’t like where the country is now as opposed to four years ago, as opposed to anytime in history, you will understand the seriousness of where we are.”

Leigh Ann Caldwell contributed to this report.