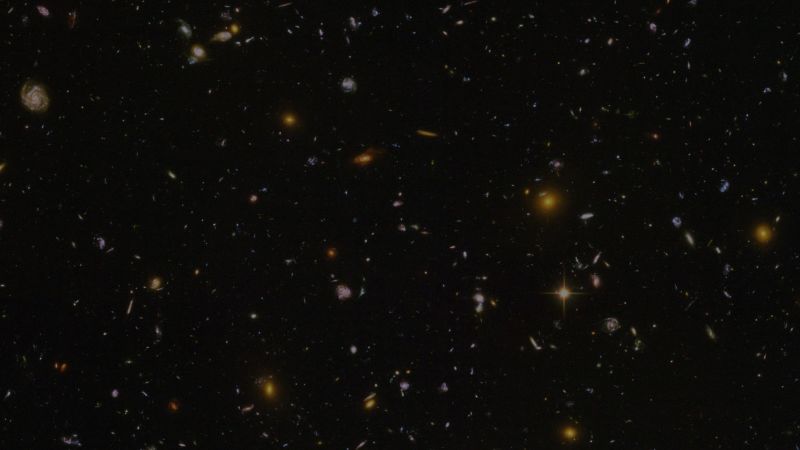

Scientists say they’ve traced the origins of a potentially hazardous near-Earth asteroid to the far side of the moon

An unusual asteroid traveling near Earth is thought to be a chunk of the moon, but exactly how it ended up zooming through the solar system has remained a mystery. Now, researchers say they’ve made a key connection in this cosmic puzzle.

The space rock, known as 2016 HO3, is a rare quasi-satellite — a type of near-Earth asteroid that orbits the sun but sticks close to our planet.

Astronomers first discovered it in 2016 using the Pan-STARRS telescope, or Panoramic Survey Telescope and Rapid Response System, in Hawaii. Scientists call the asteroid Kamo’oalewa, a name derived from a Hawaiian creation chant that alludes to an offspring traveling on its own.

While most near-Earth asteroids originate from the main asteroid belt — between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter — new research has revealed that Kamo’oalewa most likely came from the Giordano Bruno crater on the moon’s far side, or the side that faces away from Earth, according to a study published April 19 in the journal Nature Astronomy.

It’s the first time astronomers have traced a potentially hazardous near-Earth asteroid to a lunar crater, said lead study author Yifei Jiao, a visiting scholar at the University of Arizona’s Lunar and Planetary Laboratory and a doctoral student at Tsinghua University in Beijing.

“This was a surprise, and many were skeptical that it could come from the moon,” said study coauthor Erik Asphaug, professor at the University of Arizona’s laboratory, in a statement. “For 50 years we have been studying rocks collected by astronauts on the surface of the moon, as well as hundreds of small lunar meteorites that were ejected randomly by asteroid impacts from all over the moon that ended up on Earth. Kamo’oalewa is kind of a missing link that connects the two.”

In addition to helping confirm Kamo’oalewa’s potential relationship to the moon, the findings could ultimately lead to other revelations — including how the ingredients for life made their way to Earth.

Once upon a crater

Measuring between 150 and 190 feet (46 and 58 meters) in diameter, Kamo’oalewa is about half the size of the London Eye Ferris wheel. During orbit, it comes within 9 million miles (14.5 million kilometers) of Earth, making it a potentially hazardous asteroid astronomers keep track of and learn more about in case it ever strays too close to our planet.

Previous research focused on the asteroid’s reflectivity, which unlike typical near-Earth asteroids is similar to lunar materials, as well as the space rock’s low orbital velocity in relation to Earth, a quality that suggests it came from relatively nearby.

For the new study, astronomers used simulations to narrow down which of the moon’s thousands of craters could have been the asteroid’s point of origin.

Based on the modeling, the team determined that the impactor that potentially created the asteroid would need to be at least 0.6 miles (1 kilometer) in diameter to dislodge such a massive fragment. When the object hit the moon, it likely dug Kamo’oalewa out from beneath the lunar surface, sending the space rock flying and leaving a crater larger than 6 to 12 miles (10 to nearly 20 kilometers) in diameter.

These simulations also helped the team search for a relatively young crater, given that the asteroid is only estimated to be a few million years old, while the moon is believed to be 4.5 billion years old.

These parameters helped researchers zero in on Giordano Bruno, a 14-mile-wide (22-kilometer-wide) crater estimated to be 4 million years old, as the likely spot where Kamo’oalewa started its journey.

The anatomy of an impact

The study’s simulations showed that Kamo’oalewa was excavated from the lunar surface at several miles per second.

“You’d think the impact event would pulverize and distribute the (lunar material) far and wide,” Asphaug said. “But there it is. So, we turned the problem around and asked ourselves, ‘How can we make this happen?’”

Based on their models, the team believes the impact event sent tens of hundreds of 32.8-foot (10-meter) fragments flying into space. Yet Kamo’oalewa survived as a massive, singular fragment.

“While most of that debris would have impacted the Earth as lunar meteorites over the course of less than a million years, a few lucky objects can survive in (sun-centric) orbits as near-Earth asteroids, yet to be discovered or identified,” Jiao said.

Understanding how such a giant chunk of the moon could remain intact enough to become an asteroid could help scientists studying panspermia, or the idea that the ingredients for life may have been delivered to Earth as “organic hitchhikers” on space rocks such as asteroids, comets or other planets.

“While Kamo’oalewa comes from a lifeless planet, it demonstrates how rocks ejected from Mars could carry life — at least in principle,” Asphaug said.

Kamo’oalewa specimen: A connecting puzzle piece

Studying crater impacts on the moon can also help scientists better understand the consequences of asteroid impacts should a space rock pose a threat to Earth in the future.

“Testing the new model of Kamo’oalewa’s origin from a specific, young lunar crater paves the way for obtaining ground-truth knowledge of the damage that asteroid impacts can cause to planetary bodies,” said study coauthor Renu Malhotra, a planetary sciences professor at the University of Arizona, in a statement.

China’s Tianwen-2 mission, launching in 2025, will visit Kamo’oalewa with the aim of collecting samples from the asteroid and eventually returning them to Earth.

“It will be different in important ways from any of the specimens we have so far — one of those connecting pieces that help you solve the puzzle,” Asphaug said.

Studying a sample excavated from the lunar far side could reveal insights into a part of the moon that has been less studied and shed light on the composition of its subsurface. Given that the impact likely happened a few million years ago — relatively young on astronomical timescales — the samples could also help scientists study how space radiation causes weathering and erosion on asteroids over time.

“The exciting thing is that when a space mission visits an asteroid and returns some samples, we have surprises and unexpected outcomes, that usually go beyond what we were anticipating,” said study coauthor Dr. Patrick Michel, astrophysicist and director of research at the National Centre for Scientific Research in France. “So, whatever Tianwen-2 will return, it will be an extraordinary new source of information, as all asteroid missions so far.”

For a long time, astronomers thought it was impossible for meteorites to come from the moon until lunar meteorites were found on Earth, said Noah Petro, NASA project scientist for both the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter and Artemis III. Petro was not involved in the study.

The hope is that future samples could confirm the lunar origin of Kamo’oalewa.

“Going there and finding out is absolutely a way to go about it now,” Petro said. “It’s a great, great reminder that we live in a very exciting solar system and we live in a very exciting corner of the solar system with our moon. There’s no other place, no other planet in our solar system with a moon like our moon. And things like this are great reminders of how special the Earth-moon system is.”