McDonald’s to close three CosMc’s locations — and open two more

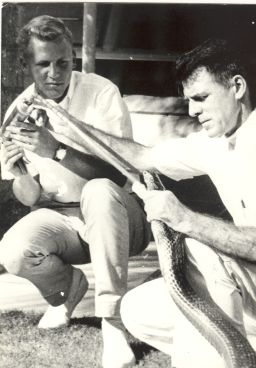

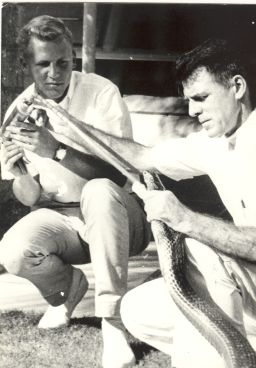

From hunter to guardian: How the ‘Snakeman of India’ found his way into wildlife conservation

Whitaker would go on to earn the nickname “Snakeman of India,” and spend more than six decades dedicated to reptile research and conservation. He’s written several books on snakes, spearheaded a lifesaving anti-venom program, and launched wildlife research stations throughout the country.

His field work with snakes and crocodiles ultimately led his conservation efforts to help save India’s rainforests.

Today, Whitaker’s focus is on educating Indians on how to protect themselves from snakes — part of a national campaign to reduce the snakebite mortality rate.

The following interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Whitaker: I started out as a very young lad in northern New York state, turning over rocks and finding bugs and stuff, until I found a snake, and it was love at first sight.

It really started then. But I must blame or thank my mother for when I first brought a snake home. She said, ‘wow, how beautiful.’ And now, which mother would do that? Not very many.

Then, when my mother married Rama Chattopadhyay and we moved to India, that was something that opened up the world to me. Can you imagine an eight-year-old arriving in Bombay and being able to go out into the jungles of India? These are dreams that I had when I was a little kid, which came alive.

Whitaker: A herpetologist is a strange person who studies reptiles. I’ve concentrated most of my work on snakes and crocodiles, but I am very interested in all the others … the turtles, the lizards, and of course the amphibians, the frogs and toads.

I’ve been doing this forever, ever since I was four years old when I picked up my first snake. [In 1960] I was going to college in America, but I flunked out. Then I got a job at the Miami Serpentarium and worked for this gentleman [Bill Haast] who handled king cobras with the greatest of ease and extracted their venom.

That was part of the love affair that I generated for king cobras. But I had always yearned to come back to India and get out to Western Ghats, where I knew king cobras still lived, and start studying them.

In 1969, I set up India’s first snake park, the Madras Snake Park. And we’ve learned more about king cobra behavior and about their wonderful lifestyle than had ever been known by anybody before.

Whitaker: I don’t think I’ve ever been scared of a snake. I’ve been scared of myself sometimes doing stupid things. I saw a black-tailed [snake] disappearing into the bushes, and I thought, ‘ah, big rat snake.’ And I dove on it, typical football tackle, grabbed it by the tail and suddenly this hooded snake rises up over me and I looked up and said, ‘oh no, I think I’ve caught the wrong tail.’ And I let it go. It was a king cobra, the first one I had ever found. It was scary. Okay, I am scared sometimes.

Whitaker: The Irulas are an aboriginal tribe here in South India. Their expertise is finding and catching snakes and their specialty [was] catching snakes for their skins. But they had run out of a way to make a living because the snakeskin industry had been banned [in 1972]. So we hatched an idea together to set up a venom cooperative, the Irula Snake Catchers Cooperative, wherein they would catch snakes from the wild, extract the venom, and then release the snakes back to the wild. And the venom, it was used to make anti-venom to save millions of lives.

Whitaker: Up until recently, we really didn’t know how many people are getting killed and injured by snakes. The Centre for Global Health Research and the University of Toronto started doing this Million Deaths Study. And I’m a coauthor of two of the major papers produced out of this study, and it turns out that close to 50,000 people are actually killed by snake bite every year in India.

Now that we know the figure, we are working very hard right now on an educational program, which is nationwide, trying to teach people how to avoid snakes and avoid getting bitten. It’s fairly simple: at night when you walk around, use a light. When you sleep, use a mosquito net. We tell people when they’re working in the field, when they’re doing agriculture, use a stick. Don’t use your bare hand because a snake could be there. So it’s just educating people. These are simple methods.

Whitaker: My early, formative years were not very conservation-oriented. I was the kid with a gun, and I would go out there and instead of being a bird watcher, I was a bird shooter.

The transition from being from a hunter to a conservationist happened [in the 1970s] when I realized that things were really out of hand here, and crocodiles were almost extinct by that time. And we really had to do something about it.

I realized that unless I got into conservation, there’s not going to be anything left. I set up field stations along with my colleagues and they are magnets for people who want to get into working with reptiles. And we’ve had dozens and dozens of people who have now turned out to be some of the greatest conservationists in India we can call graduates of these stations.

Whitaker: People will remember me, like it or not, as a snake freak. But it’s wonderful to think [of] the influence that I have had or that our organizations have had to engender this incredible deep interest in something which people sneered at or ran away from all their lives, but now suddenly, hey, they’re interesting, they’re hip, they’re in. Snakes rule!

And it’s wonderful to realize that dozens, if not hundreds, of young people have continued to do wonderful work with reptiles. It’s just wonderful.