The Ukraine war is a huge opportunity for US intel to recruit Russian spies

Russia’s brutal ongoing invasion of Ukraine has provided US intelligence services with a rare opening to recruit Kremlin insiders furious with the handling of the war.

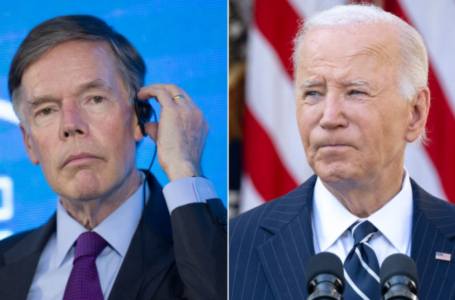

“Disaffection creates a once-in-a-generation opportunity for us,” said CIA Director Bill Burns last year during a speech in the United Kingdom. “We’re very much open for business.”

“That business is the exchange of information that the asset or agent would provide for something that they want,” said David McCloskey, former CIA officer and author of Moscow X. “We want people who have some sense of what [Russian] leaders’ priorities are – what they’re trying to accomplish.”

The ongoing recruitment effort is far from a state secret. The CIA has released Russian-language videos on social media appealing to the patriotism of disaffected Russians with access to information that could be helpful to the US.

The effort highlights the evolution of an intelligence service that has historically conducted its essential mission of countering national security threats and informing policymakers under a shroud of secrecy.

Indeed, until the CIA’s internally unpopular and short-lived director, James Schlesinger, finally posted a sign on a highway marking the site of the ultra-secret organization’s Virginia headquarters in 1973, its very location had been shielded from the public.

Fast forward to today, when the spy agency is not only ubiquitous across social media platforms, it is actively using its newfound public-facing presence to accomplish one of CIA’s primary objectives: recruiting foreign spies to steal secrets.

Posts have included step-by-step instructions for would-be Russian informants on how to avoid detection by Russia’s security services by using virtual private networks, or VPNs, and the Tor web browser to anonymously and through encryption contact the agency on the so-called Dark Web.

The FBI launched a similar effort aimed at recruiting Russian government sources in the US, including geo-targeting social media ads to phones located near Russia’s embassy in Washington.

“This direct appeal is an unusual approach, but one which could prove effective in reaching a Russian populace with few options to express their discontent,” said Douglas London, a former CIA station chief posted abroad. “Russians angry with the Kremlin’s state-sanctioned corruption and abuse, with no way to act openly, are left with few alternatives other than finding external support.”

But while the technology is new, espionage has underpinned, and often undermined, US-Russian relations for decades.

With never before heard interviews from Cold War spies and the traitors who sealed their fate, “Secrets and Spies” tracks the operatives who worked behind the scenes to steal and share vital intelligence as the world stood on the brink of nuclear war.

Like the Cold War of the past, espionage remains a vital tool for both sides of the latest conflict, as evidenced by tech-savvy US intelligence officers attempting to recruit new assets in plain sight, and Russian-linked operatives reportedly increasing operations across Europe.

While espionage is illegal in every nation in the world, and undercover operatives have certainly been used for nefarious purposes such as sabotage, assassination, and election interference, “Secrets and Spies” pulls back the veil on a lesser-known, historically critical function of spying: to reduce uncertainty and miscalculation among nuclear-armed adversaries.

As the documentary underscores, the espionage lessons of the Cold War could very well determine future global stability.