The Olympics have long promoted safe sex. Now it wants to focus on pleasure.

The City of Love has a message as it prepares for the Olympics: Performance is not always the priority. Rather, when it comes to sex, pleasure takes first place.

As Paris starts welcoming athletes to the Olympic Village in the coming days, organizers of the 2024 Games are set to launch a comprehensive sexual health campaign that champions pleasure and consent as well as the traditional emphasis on safety.

It is an important message, backed by research, that is rarely endorsed on a stage with a global spotlight as influential as the Olympics.

Prioritizing pleasure in sexual health refers to the approach of celebrating the physical and mental benefits of sexual experiences as well as minimizing the risks. It aims to rewrite fear and shame narratives that cast sex as taboo, with sexual health organizations promoting the sex-positive method as fundamental for unlocking greater agency over sexual rights and well-being.

A systematic review by the World Health Organization and advocacy group The Pleasure Project found that pleasure-inclusive sex education is a more effective sexual health intervention strategy than abstinence programs and risk-focused messaging. The findings show that it increases condom usage and enhances knowledge and self-esteem, which are crucial to promoting safer choices in the bedroom.

The decision to focus on pleasure-inclusive messaging at the Olympics is especially significant at a time when sex education is increasingly under attack in many countries. In the United States alone, 2024 has seen a surge in restrictive state-level sex education proposals that aim to limit what can be taught in the classroom, such as by removing guidance around contraception or advocating for abstinence.

History of Sex Ed at the Olympics

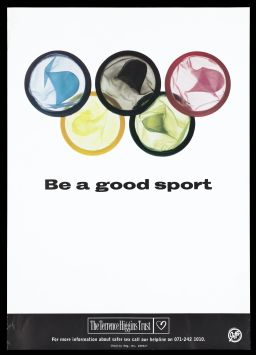

Paris’s focus on pleasure and consent is part of the Olympics’ long-running history of promoting safe sex, with organizers of the 1988 Seoul Games first making headline-grabbing hand-outs of condoms to competitors to raise awareness of HIV and AIDS.

Since then, the International Olympic Committee has encouraged host cities to roll out condom initiatives at all summer and winter games, from a record-breaking 450,000 condoms at the 2016 Rio Olympics – equivalent to 42 per athlete – to keeping up the tradition at the 2022 Beijing Olympics despite COVID-19 social distancing rules.

This year, organizers in charge of first aid announced that over 200,000 male condoms, 20,000 female condoms, and 10,000 dental dams would be made available at the Paris Olympic Village, which will host around 14,500 athletes. They will also have numerous sexual health testing centers on site for athletes, in addition to the sexual health awareness messaging.

While one athlete – a gold medallist – once suggested sex was “part of the Olympic spirit … Why do you think they give away so many condoms?” the massive number of condoms distributed is not just a reflection of the competitors’ extra-athletic activities. Instead, the initiatives are intended to be used as a springboard for sex education.

Anne Philpott is the founder of The Pleasure Project, an international organization that has spent the past two decades advocating for pleasure-inclusive sex education. She applauds Paris’ decision to pair its condom initiative with pleasure and consent messaging.

“So far the public health world has not done a good job of promoting safe sex,” Philpott said, explaining that promoting condoms “purely for avoiding negative consequences,” is not effective.

Rather, she says the most productive way to encourage safe sex is to flip the script from the beginning by focusing on why people have sex.

“People think pleasure is a bit frivolous or the icing on the cake. But we now know that if we had integrated pleasure considerations into sexual health interventions from the beginning of the AIDS epidemic, we would have saved considerably more lives,” Philpott explained.

“There’s been a big rise in choking being seen as a normal part of sexual activity when it’s actually very dangerous,” Philpott gave as an example, as she urged sex education curriculums to catch up with what people are able to access online.

Turning sport into a sex ed classroom

The need to learn about one’s sexual desires, needs, and boundaries is a constantly evolving process, with the Olympics’ spotlight on safe sex also highlighting the opportunity for wider sporting communities to become trusted spaces for such conversations.

In the coastal town of Kilifi in Kenya, Deogratia Okoko sees the value of expanding sex education beyond the classroom, using soccer to teach young boys about issues such as consent and contraception. The scheme to which he contributes, known as “Moving The Goalposts,” works directly with community leaders, fathers, and young boys to provide resources on sexual health, sexual rights, gender, and positive masculinity.

“We found that one of the places that they spend a lot of their time is the football pitch,” Okoko said.

“We began to design our sessions based on soccer drills to explain certain issues,” Okoko said, adding: “You’ll find that sometimes they get so engrossed in the debrief discussions that they forget that they were supposed to actually train and play.”

Moving the Goalposts

Okoko explained that the initiative also provides a safe space for boys to access condoms and HIV testing kits, with societal shame often creating barriers for boys to buy these products directly from the shops.

“It’s no longer just let’s play football, let’s practice and go away … these spaces are now a community used by them to talk about issues that they’d not normally talk about,” Okoko said.

Reflecting on the Paris organizers’ decision to include pleasure and consent in their sexual health messaging, Okoko says it is “imperative” to have high-profile platforms set the example.

“It’s fundamental. It’s important. It’s good if we, to the best of our abilities, find great ways of passing that message across,” Okoko said.