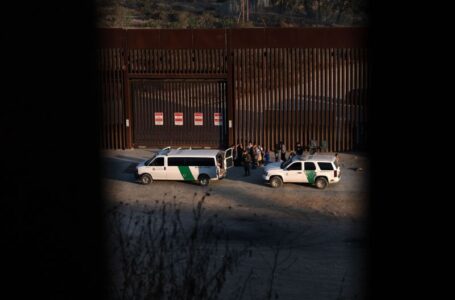

Mexican border town declares state of emergency as Trump pledges mass deportations

This remote, mystical forest has been protected for centuries. Now it’s under threat

“Call to Earth Day – Connected Generations” celebrates the links between people and cultures and how these can help to play a vital role in preserving our planet.

Naimina Enkiyio, or the “Forest of the Lost Child,” stretches along the top of an escarpment on the western wall of the Rift Valley, Kenya. Legend has it that the forest is haunted by the spirit of a young girl lost while herding her family livestock. This place is sacred to the indigenous Maasai people, of whom around 25,000 live in and around it. Despite being just 70 or so miles southwest of the capital Nairobi, a lack of roads means these are some of the most remote Maasai clans in the whole of Kenya.

Not used to human presence, the forest’s animals are shy and know how to avoid our noisy footsteps. It’s hard to make out any creature, but there are signs of them everywhere. Piles of fresh elephant and buffalo dung obstruct the path. Chirps echo from the canopies, indistinguishable grunts and rustles come from within the overgrowth, and a gentle revving sound can be heard as colobus monkeys swing between branches overhead. High up in the Loita hills, this is the closest you’ll come to hearing a motorbike.

Parmuat Ntirua Koikai, a Maasai elder, leads the way. The 58-year-old’s earlobes are weighed down by bright beads and his back is draped in a red-checked shuka (a traditional cloth robe). He can’t speak English, but he uses simple motions to communicate the knowledge inherited from his forefathers. He picks a leaf from a shrub, mimes eating it and rubs his tummy: Obibi naibor, used to treat diarrhea. He points at the roots of a tree, then to his back with an expression of pain: Olmorogi, for soothing aches.

Ntirua Koikai sees himself as a custodian of the forest. He and most of the community believe it is their duty to protect it – and in turn, they believe the forest will protect them.

“Without the forest there would be no people,” he says in the Maa language, through a translator. “We use it as a clinic, a hospital, so we must handle it with a lot of care.”

This deep-seated respect for the forest has earned it protection. Unlike many other forests in Kenya that have been logged or developed, Naimina Enkiyio remains largely intact. According to analysis of Hansen Global Forest Change data by the Mara Elephant Project, it has only lost 2% of forest cover since 2000, while some others in Kenya have lost 20 to 60% in the same timeframe.

But there is a growing fear among the community and conservationists that this could soon change, due to threats from land privatization, cultural shifts and the climate crisis.

That could have huge effects on the wider ecosystem. Located between the wilderness of the Serengeti and the Maasai Mara, the forest is a critical watershed, feeding the parched plains below where livestock graze and vast herds of wild animals migrate.

“It is a crucial drought reserve for elephants and a lot of the wildlife that comes up from the Mara Serengeti ecosystem,” explains Rob O’Meara, a conservationist who, together with his wife Sarah, both Kenyans, lives at the center of the forest with permission from the Maasai. He describes how, as climate change causes longer and harsher periods of drought, the forest could provide a lifeline to both humans and animals.

In photos: The plants and animals of Naimina Enkiyio

Shared land

In a shady clearing, a group of Maasai elders sit in a circle on the grass. Their rungus, short wooden clubs used for hunting, lie by their sides. Speaking in turn, respectfully, they all agree: the biggest threat to the forest is land adjudication, a Kenyan government policy whereby communal land is subdivided into individual plots.

The practice began during the British colonial period and was designed to convert land into a valuable asset that could stimulate rural development and prevent boundary conflicts. But critics warn of its ecological consequences, leading not only to an increase in fenced enclosures that prevent wildlife movement, but also roads, crop farming and timber trade. In 2020, the Loita area in southwest Kenya was marked out for adjudication by the government, and the process of apportioning land has since begun. The local Narok County Government did not respond to requests for comment.

The elders say this policy goes against the Maasai tradition of communal ownership, representing a disregard for their culture. Eighty-five-year-old Oltukai Ole Koikai, the eldest of the group, speaks first: “If you own the land, you can do whatever you want to do: you can sell it, you can give it to a different person outside the community … They don’t know our culture, they don’t know the forest, all they know is maize and beans.”

Already, agriculture has started to take over the society’s pastoral practices. Traditionally, the Maasai were nomadic cattle herders, who trailed through Kenya’s savannas seeking fresh pasture and making temporary manyattas (small mud houses) wherever they went. Today, due to development and prolonged periods of drought that have diminished the grasslands that feed the cattle, their lifestyle has become more sedentary, and they are looking for ways to diversify their income, including growing crops.

With a shift away from grazing, the elders fear that the value of the forest will be forgotten. They recall the times when they would go into the hills as boys to graze their cattle. It was there that in dry periods they could always find lush pastures.

But today, with fewer cattle, the younger generations of Maasai are coming into the forest less. The elders lament that while the forest hasn’t changed – they say all the plants that were there when they were children are still there today – people have.

Digital age

Ole Koikai blames the “digital” generation who he says now consult their phones rather than their elders. He worries that they will not learn the ways of the forest and how to live alongside it.

This knowledge, from understanding plants to how to interact with the forest’s many wild animals, has been passed down orally through the generations. While the community’s cultural ceremonies continue to take place in the forest, such as rituals after children are circumcised and the worship of sacred trees during times of drought, the overall time spent in the forest is rapidly decreasing.

The laibon, the Maasai’s spiritual leaders and healers, source medicinal herbs, trees and plants from the forest to treat diseases and ailments. They say it is the peace of the “lost child” (the forest’s namesake) that brings power to these remedies. But fewer people are becoming laibons, as they opt for a different lifestyle.

“The current generation just go to the city,” says Ntirua Koikai. “They don’t come here to learn the culture, learn species in the forest … They’re not interested at all.”

He hopes there may be some way to record the information in a document so that future generations can understand, as “knowledge without writing may disappear.”

There have been some efforts to do this. In 2019, the Kenya Forestry Research Institute published the first comprehensive checklist of plant species in Naimina Enkiyio, compiled through a survey from 2012 to 2015. It identified a total of 277 plant species, with both their botanical names and local Maasai names.

The report’s author, Mbuvi Musingo, hopes this will go some way to preserving the indigenous knowledge and provide a reference point for species in the future. “Naimina Enkiyo is a very important site not just in Kenya, but globally,” he says, explaining that the survey found that some plant species, which are endangered across the rest of the country, grow in abundance there.

New values

Living and working closely with the community in the forest, conservationist O’Meara has observed the Maasai’s customs for a decade, and yet it is still hard for him to explain exactly what they do to protect it. “The laibons play a very large role, with their spells and their medicines, but there is also just a respect for the forest – it’s almost hereditary.

“It is dying fast with the Western culture that is creeping in,” he cautions. “Part of protecting the forest is going to be how to maintain that culture of respect.”

For O’Meara this boils down to creating new values. “In the past, the cultural respect for the forest has been (as) a drought grazing area, a source for medicine … but that value is dying,” he says. “We’re going to have to maintain that value, but also give it a monetary value, which is where tourism, conservation, biodiversity credits, carbon trading (come in).”

The O’Mearas, alongside conservation organizations such as the Mara Elephant Project, have been working on creating alternatives that will incentivize the community not to clear the forest for timber or crops. That could include a sustainable wood fuel scheme, whereby the outer edges of the forest are coppiced and sold, or encouraging the community to keep beehives and sell honey, which could generate more income than maize.

They are exploring the possibility of setting up conservancies across the Loitas – a system that is used widely across Kenya, whereby a conservation group or tourism operator leases land from local communities and operates it as a wildlife reserve, while sharing any profits with the community; and a carbon credit project, that would bring a monetary value to keeping the trees standing, is also in the works.

But all of this, O’Meara stresses, is entirely dependent on community support: “The Maasai have a system where if they make a decision, they always look for 100% consent from within their communities.” For any of this to work, they will need to be involved each step of the way, he says.

Josephat Olokula, 25, is one of a handful of Maasai youths who is committed to maintaining the forest. He is a sparky young man dressed in Western clothes, with a smartphone poking out of his front pocket. Having done very well at a local school, he says he became the first person from his village to go to university. But while many of his peers decided to move to a city, he has come back to the community to learn from the elders and protect the forest. He now has a job working on the carbon trading scheme.

“If you’re not engaging with the elders here then it would be difficult to learn the culture and how to protect the forest,” he says in English, but he adds that while he is learning from them, they can also learn from him. “I’m engaged with the issue of climate change. The only area that will save us is the forest. I really need to tell people that the forest must be there for us to have our health.”

Blessing the forest

The generational divide is not going away anytime soon. Modernization is unavoidable – the younger men with phones are all eager to show off their Facebook profiles. But if there are attractive opportunities available to the younger generation within their communities, perhaps the cultural values and respect for the forest will live on.

Ntasikoi Oloimoeja, 30, is a laibon, one of the youngest of the community’s spiritual leaders. He has a strong, soulful gaze and white markings painted on his forehead and around his eyes. He sits with a large horn in his hands, full of all sorts of pebbles and charms. The laibon have a tradition of “stone throwing,” where they ask the stones a question, toss them onto a cloth and after a process of counting, interpret what the stones say.

“When we wake up, we ask our stones if there’s anyone with intention to come and grab the forest,” he says. “Then we ask the forest to keep giving us rain.”

Along with two of the elders, Oloimoeja stands up and starts to perform a blessing for the forest. He places a cowrie shell full of white powder upon the ground and they start pacing around a tree, chanting, kneeling over the cowrie shell on each lap.

“We shall protect the forest so that we retain this fresh air for our communities and also everyone in the world,” he says. “This is our forefathers’ forest … we must support what they left for us.”