Dems eerily silent on Trump sentencing as they prepare for Republican trifecta in Washington

Julian Assange’s mission was to change the world – but at what cost?

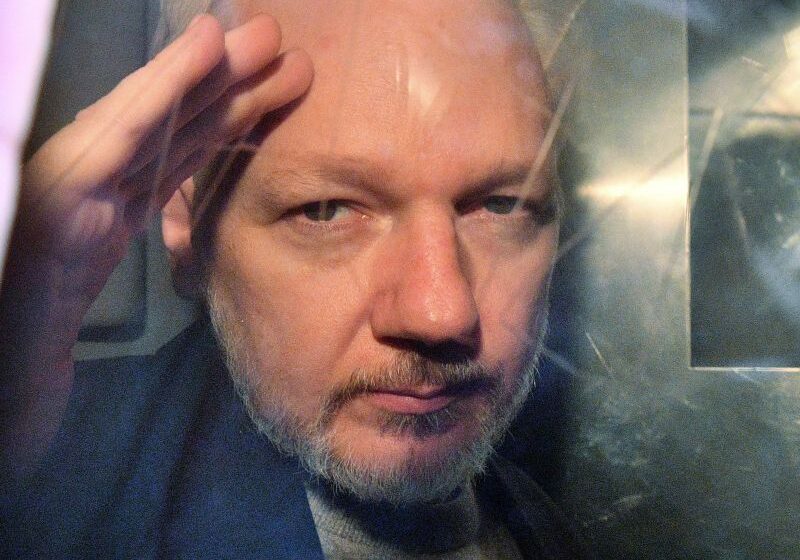

Julian Assange started his WikiLeaks whistleblowing website on a quest for “radical transparency and truth,” a mission that turned an already polarizing personality into a notorious character and earned him crusaders and critics in equal measure.

The long-running battle for his extradition to the United States continued this month, with US lawyers providing the UK High Court with a series of assurances around the 52-year-old WikiLeaks founder’s First Amendment rights and that he would not receive the death penalty if he were handed over. Those are set to be reviewed at a fresh hearing on May 20.

It has been 12 years since the embattled Australian has been able to walk freely. He’s spent the past five years in London’s high-security Belmarsh prison and nearly seven years before that holed up at the Ecuadorian embassy in the English capital, trying to avoid arrest.

He faces life imprisonment in the US for publishing hundreds of thousands of sensitive military and government documents supplied by former Army intelligence analyst Chelsea Manning more than a dozen years ago. But recently there has been increased pressure for Assange’s case to be dismissed.

Just this month, President Joe Biden offered Assange’s supporters a glimmer of hope saying his administration was “considering” a request from Australia to drop its charges against the WikiLeaks founder. The remarks were described as an “encouraging” signal by Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese, who added that Assange had “already paid a significant price” and “enough is enough.”

The ascent of Assange

Born in Townsville, eastern Queensland, in 1971, Assange had a less than conventional upbringing. His education was a combination of home schooling and correspondence courses, since his family moved frequently.

In his teens, he discovered a natural proficiency for computing, but his activities – which included accessing several secure systems, including the Pentagon and NASA, under the hacker alias “Mendax” – soon put him on the radar of authorities. In 1991, he was charged with 31 counts of cybercrime by Australian authorities but only received a small fine at sentencing after pleading guilty to most of the charges.

Following his brush with the law, Assange worked as a computer security consultant, traveled and briefly studied physics at the University of Melbourne before withdrawing from the course.

His vision when starting WikiLeaks in 2006 was that it would be a kind of online repository, which would publish anonymously submitted documents, video and other sensitive materials after vetting them.

It ran for several years, uploading material ranging from the US military’s operating manual for its detention camp in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, to internal documents from the Church of Scientology and some of 2008 Republican vice-presidential nominee Sarah Palin’s stolen emails.

On first impressions, Assange was “vague” and “elusive,” Shubert recalled. With the benefit of hindsight, she now believes his behavior was the result of “sitting on this cache of documents from Chelsea Manning and trying to figure out how to publish it.”

WikiLeaks ultimately released the video from the US helicopter attack in Iraq, sparking condemnation from human rights activists and earning rebuke from US defense officials. By the year’s end, the organization had gone on to publish nearly half a million classified documents relating to the US wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Under a global spotlight

As WikiLeaks continued its disclosures, Assange found himself the latest cause célèbre – his every movement intensely scrutinized. And with each headline, his infamy grew among those who did not share his vision.

Fidel Narvaez, former consul of the Ecuadorian embassy in London, met Assange in 2011, after WikiLeaks released another huge archive – this time of secret US diplomatic cables. The pair became close friends through the years.

Assange’s story, as the “teen hacker who became insurgent in information war” as the Guardian put it in 2011, sounded like the plot of a Hollywood blockbuster. Soon his tale was immortalized in documentaries and films, perhaps most notably in 2013’s “The Fifth Estate,” which Assange labeled a “geriatric snoozefest” that used what he considered flawed source material.

For journalist and author James Ball, who briefly worked at WikiLeaks and was based for a time at Ellingham Hall, a remote manor house north of London where Assange holed up before seeking refuge in Ecuador’s embassy, the infancy of WikiLeaks was an “exhilarating” time.

WikiLeaks became a household name thanks to its frequent data dumps, but some were starting to question the founder’s behavior. For many, his polarizing personality became an issue.

Ball added: “He sort of liked the attention. … He liked the fuss that (the disclosures) caused but he was oddly incurious actually about the documents.”

Others offer alternative explanations for Assange’s eccentricities. Narvaez said the Assange he knew was “hyperactive and workaholic” and pointed to his diagnosed autism spectrum disorder as an element of his personality.

Shifting attitudes

Such questions aside, WikiLeaks essentially ground to a halt when Assange was accused of sexual assault in Sweden in August 2010. The organization’s focus shifted from offense to defense, despite the transparency campaigner’s vehement denial of the allegations against him. There were mounting calls for Assange to leave WikiLeaks and, when he didn’t, many cut ties with it.

Assange labeled it “a smear campaign” orchestrated to pave the way for his further extradition to the US and refused to go to Sweden for questioning.

In June 2012, while out on bail from UK officials over the Swedish probe, he opted for a nuclear option and knocked on the door at 3 Hans Crescent, where he requested political asylum from Ecuador.

Outside the confines of his diplomatic shelter, the world questioned whether Assange was trying to circumvent justice.

Over time, his relationship with his host soured along with the arrival of a new president in Ecuador in 2017. Assange was “an inherited problem” for Lenin Moreno, who was facing pressure from the US to expel him from the diplomatic bolthole.

“It was obvious that former President Moreno was going to give in to external and internal pressure,” Narvaez said.

Narvaez, seen as too close to the unwanted houseguest, was asked to leave in July 2018 amid a shake-up of the diplomatic mission’s staff. “I left him isolated, and I was the last person he trusted,” Narvaez said.

Nine months later, in April 2019, Assange was pulled kicking and screaming from the building by London’s Metropolitan Police on an extradition warrant from the US Justice Department.

Legal limbo

Assange has since lived, mostly isolated, in a three-by-two-meter cell at Belmarsh prison in southeast London. The prison has the capacity to hold over 900 inmates and is known for once housing infamous terror suspects such as Abu Hamza al-Masri within its high-security unit.

The US has accused Assange of endangering lives by publishing secret military documents in 2010 and 2011. He is wanted on 18 criminal charges relating to his organization’s dissemination of classified material and diplomatic cables. If convicted, he could face up to 175 years in prison conditions much harsher than here in the UK.

Fighting his corner since he entered Belmarsh: his wife, Stella Assange. The couple married in March 2022, while he was in prison.

Stella, the mother of Assange’s two young sons, called her husband a “political prisoner” outside court last month and has repeatedly voiced her fear that, if extradited, he could take his own life.

She labeled the US’ latest guarantees that Assange could lean on First Amendment protections at trial “blatant weasel words” in a statement on April 16.

“The diplomatic note does nothing to relieve our family’s extreme distress about his future – his grim expectation of spending the rest of his life in isolation in US prison for publishing award-winning journalism,” she said.

Assange’s team argue he is being extradited for political reasons and that a handover to the US violates the European Convention on Human Rights. It’s a claim supported by independent experts.

The UN Special Rapporteur on Torture, Alice Jill Edwards, in February called on the British government to halt a possible extradition and reiterated her concerns about Assange’s fitness and “the potential for him to receive a wholly disproportionate sentence in the United States.”

Marking Assange’s five years at Belmarsh, Amnesty International’s Secretary General Agnès Callamard warned that Assange, if extradited, would “be at risk of serious abuse, including prolonged solitary confinement, which would violate the prohibition on torture or other ill-treatment.” She added that US assurances over his treatment could not be relied upon as they are “riddled with loopholes.”

Far-reaching repercussions

Beyond the personal costs for Assange, many have expressed concern about the broader implications for press freedom around the world if he is sent to the US.

Five international media organizations that collaborated with Assange have called the US government to end its prosecution of him for publishing classified material. In a 2022 letter, representatives for The New York Times, the Guardian, Le Monde, El País and Der Spiegel argued publishing is not a crime.

“Obtaining and disclosing sensitive information when necessary in the public interest is a core part of the daily work of journalists. If that work is criminalised, our public discourse and our democracies are made significantly weaker,” the letter stated.

Jameel Jaffer, executive director of the Knight First Amendment Institute at Columbia University, said anyone who cares about press freedoms should not be comforted by the First Amendment assurances offered by US lawyers.

He continued, “And if the government is successful, no journalist will ever again be able to publish US government secrets without risking (their) liberty.”