Scientists expect major ‘medical breakthroughs’ despite Trump’s cap on NIH research funding

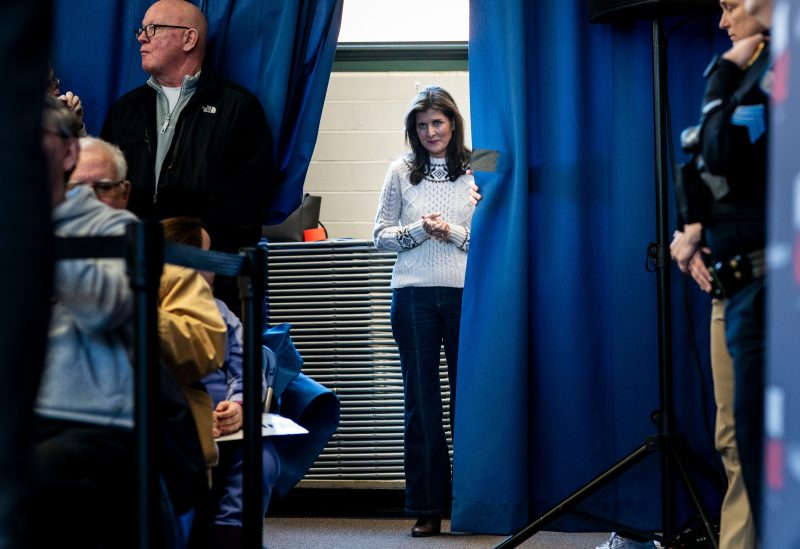

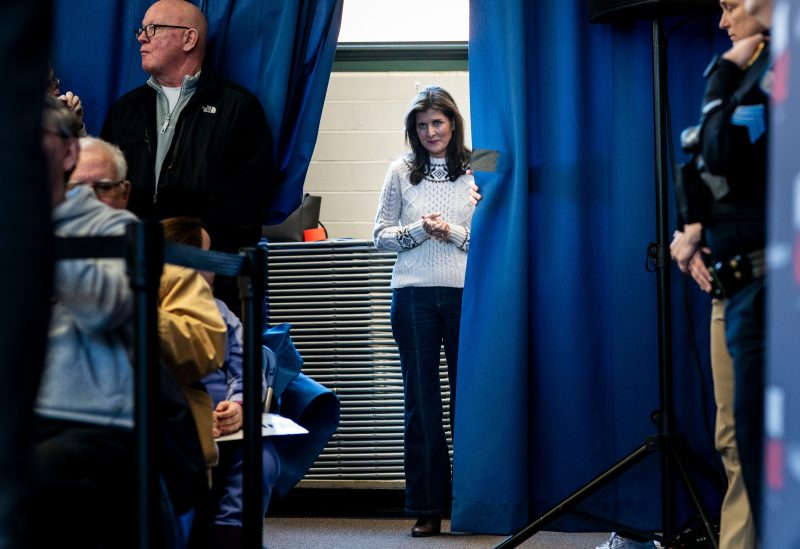

Nikki Haley to suspend campaign for 2024 Republican presidential nomination

Nikki Haley, a former U.N. ambassador and governor of South Carolina, will suspend her presidential campaign Wednesday morning, according to several people familiar with her plans, leaving Donald Trump with no major opponents left on his path to becoming the 2024 Republican nominee.

The only woman in the Republican race and Trump’s final remaining major GOP rival, Haley campaigned on her foreign policy experience and general-election appeal, casting her candidacy as a generational change that could bring more voters into the Republican fold. She was the first candidate to announce a challenge to Trump and outlasted a large field of rivals who were viewed as more viable opponents to become the final candidate standing between him and the nomination, but her message struggled to appeal to a base that overwhelmingly supports the former president.

Haley’s decision was first reported by the Wall Street Journal and was confirmed by multiple sources familiar with her decision, who spoke on the condition of anonymity to share plans that have not been announced. Haley does not plan to announce an endorsement Wednesday, the people said.

She will deliver remarks Wednesday morning in Charleston, S.C., and will encourage Trump, who is close to having the delegates needed to win the GOP nomination, to earn the support of Republicans and independent voters who backed her.

While Haley fell short of Trump in all but two nominating contests, polls showed her strength with suburban women and independents — key groups in the general election. Haley throughout her campaign repeatedly highlighted that hypothetical head-to-head polls showed her leading President Biden by a significant margin, in large part due to such voters.

Haley remained in the race through Super Tuesday, when 15 states voted and Trump won landslide victories in most contests. Her only wins during the primary season came in D.C., where she handily defeated Trump, and Vermont, where she narrowly scored her second victory. But Tuesday’s vote further solidified Trump’s lead in the race.

Haley’s departure officially clears the path for Trump, who many in the party had already seen as the presumptive nominee after dominating the first few nominating contests. By the end of the race, Haley’s campaign had become a rallying point for the disparate anti-Trump forces in the party, including some wealthy donors, activists and others whose influence has been limited in recent years. Her defeat reflects Trump’s enduring grip on the party, even as he faces 91 criminal charges across four indictments — a factor he has used to build support from Republicans in his campaign.

Haley, the first prominent woman of color to seek the GOP nomination, came in third in the Iowa caucuses and was banking on a strong showing against Trump in the New Hampshire primary. But Trump defeated her by about 11 percentage points, consolidating support from several former rivals in the run-up to that primary, including Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, Sen. Tim Scott (R-S.C.) and entrepreneur Vivek Ramaswamy.

The former ambassador then suffered an embarrassing second-place finish to “None of these candidates” in the Nevada presidential primary, which Trump skipped. And she fell in defeat by about 20 percentage points in her home state of South Carolina, where influential state Republicans — including Rep. Nancy Mace, who Haley previously helped save from a Trump-backed challenger, and Scott, who Haley appointed to the Senate as governor — endorsed Trump over her.

Haley launched her campaign in February 2023. The daughter of Indian immigrants, she sought to focus her pitch on her experience on the world stage and consensus-building on divisive issues such as abortion. Haley also sought to appeal to the conservative base on many issues — for instance, calling transgender athletes’ participation in girls’ sports the “women’s issue of our time,” and rejecting identity politics. The 52-year-old often pointed to her potential in a general election race — and to polls showing she could perform more strongly against Biden than her rivals could.

Haley was initially viewed as an underdog candidate, facing several challengers who polled better in the race’s early stages, including DeSantis. But last fall, thanks in part to well-received debate performances and a winnowing field, she emerged in some polls as the top GOP challenger to Trump, opening a narrow path to advancing in the race.

Long seen as a disciplined and scripted candidate, Haley had avoided creating controversy for months, largely flying below the radar as Trump and DeSantis traded barbs. But in late December, she drew a backlash in both parties when she failed to mention slavery after facing a question at a town hall about the cause of the Civil War. She acknowledged the next day that the conflict was about slavery, but her comments continued to haunt her campaign.

She also confronted attacks during the race from Trump and others that were criticized as sexist. Trump said last year that Haley was “overly ambitious” and “just couldn’t stay in her seat.” With her win in D.C., Haley became the first woman to win a Republican primary in U.S. history, and she won over young girls on the campaign trail — often at her most animated encouraging them to be “strong girls.”

As Haley’s campaign gained momentum, the attacks from Trump intensified. The former president, who has a history of using his opponents’ backgrounds to exclude or seek to ostracize, began lobbing racially charged attacks at Haley, giving her a nickname that appeared to be yet another racist dog whistle. Trump also reposted a false “birther” claim about Haley that incorrectly suggested she was ineligible to be president or vice president because her parents were not U.S. citizens when she was born. Ahead of the South Carolina primary Trump mocked Haley’s husband, a service member who is currently deployed overseas, for his absence on the campaign trail, enraging Haley and her allies.

Trump also attacked Haley on policy, suggesting that she would be weak on border security and protecting Social Security. In many ways, Haley ran on a traditional platform reminiscent of many Republican candidates who sought the presidency before Trump’s rise. She stressed a muscular approach to foreign policy, including aiding Ukraine in its war against Russia, and fiscal restraint on domestic matters.

Haley drew fresh attention late last year from wealthy donors eager to stop Trump, and she garnered larger crowds on the campaign trail in the months before the first primary votes were cast. She also won the support of the powerful political network backed by billionaire industrialist Charles Koch, which dispatched its flagship political organization to help Haley. But it would prove incapable of overcoming Trump, and the organization ended its financial support of her campaign after her loss in South Carolina.

Her political and policy shifts and lack of specifics — particularly over Trump at the start of her campaign and around abortion — drew attacks from those who claimed she was trying to have it both ways. When he first ran in 2016, Trump criticized Haley, but she joined his administration the next year and later vowed not to run against him in 2024. Then she disavowed the pledge.

Haley’s attacks on the former president intensified in the final months of the race. After the Iowa caucuses, she ramped up her criticism, while still maintaining that they had a good working relationship during his first term and that they agreed on many policies. She questioned Trump’s mental fitness after he confused her and former House speaker Nancy Pelosi at a campaign rally, blamed him for Republican losses in the last three elections, and portrayed both Trump and Biden as “grumpy old men.”

Some Republican campaigns such as DeSantis sought to paint Haley as too moderate to be the GOP nominee, criticizing her for citing Hillary Clinton as an inspiration to run for office and for writing in a social media post that George Floyd’s death “needs to be personal and painful for everyone.” She brought together an unlikely coalition of supporters, including Democrats frustrated with Biden’s age, and appealed to independent voters in the early states.

Biden’s campaign branded her a MAGA extremist, pointing to her record on abortion, which includes signing a 20-week ban as governor, even as she advocated for finding consensus on the issue.

Late in the race, Haley expressly rejected the notion that she could be Trump’s running mate if he ultimately won the Republican presidential nomination.

“I have said from the very beginning, I don’t play for second. I don’t want to be anybody’s vice president. That is off the table,” Haley was overheard telling a New Hampshire voter.

After her home state loss, some Haley allies began shifting their discussion of her effort, with an official at SFA Fund, a pro-Haley super PAC, saying “there are other reasons to run than winning” and suggesting she was setting up a movement for the future.

“I’m not fighting for a Republican Party of the past. I’m fighting for a Republican Party of the future … What I have said for way too long, is the Republican Party only talks to people that look and act like them,” Haley told reporters just days before suspending her bid. “The Republican Party I want is the Republican Party that goes to places that Republicans have never talked about. It goes to African Americans, goes to Hispanics, really identifies with suburban women, talks to the younger generation, and brings them into the fold with a future that talks about new things.”

In the final weeks of her campaign, Haley argued her margins against Trump — at times around 40 percent of the primary vote, despite his dominance and quasi-incumbent status — were a warning sign for November, continuing to argue she had the best path against Biden, who she led by double digits in several hypothetical match up polls.

“Republicans can’t think that it’s everybody else’s fault because people aren’t Republican. Maybe it’s Republicans fault that we’re not communicating something that makes people want to come to us,” she added.

Hannah Knowles and Maeve Reston contributed to this report.