7,000 killed since January in fighting in DRC, prime minister says

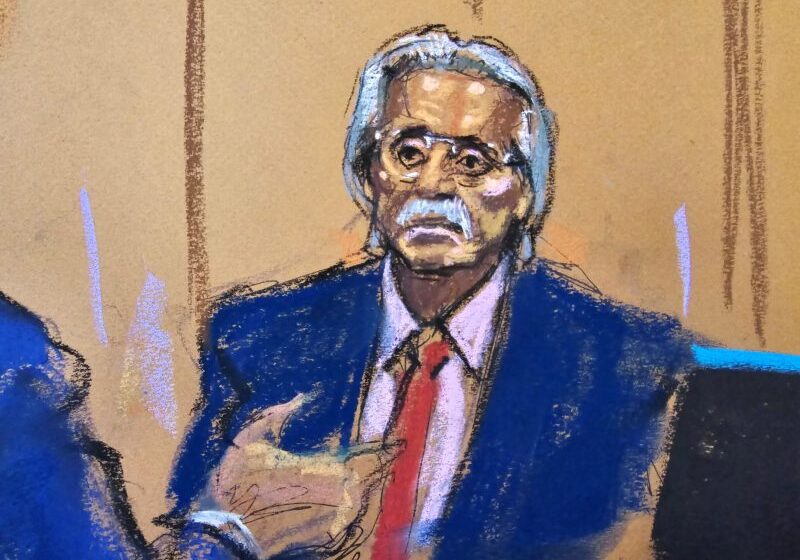

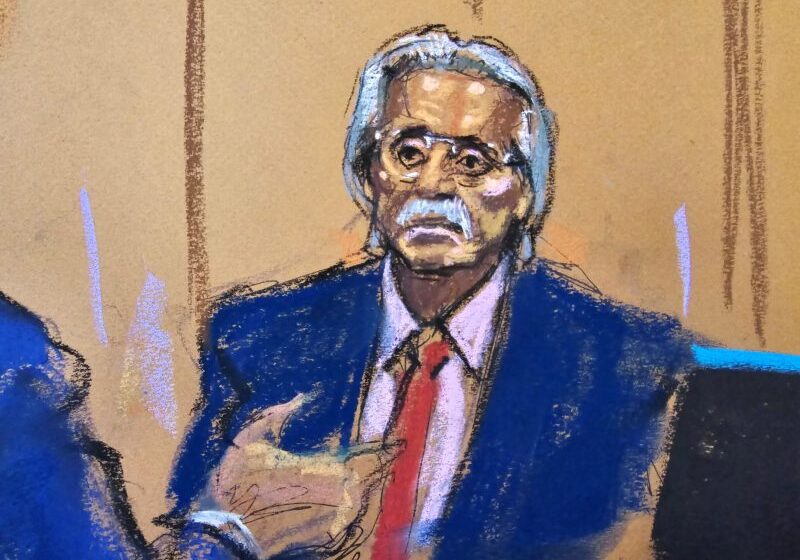

Secrets, lies and payoffs laid bare in Week 1 of Trump trial testimony

NEW YORK — Donald Trump fought mightily before and after he was elected president to keep secret the embarrassing details of his private life, but often failed despite having a fat checkbook and a well-connected tabloid editor in his pocket, according to the first week of evidence at his trial.

Former presidents typically spend their post-White House years writing memoirs, making well-paid speeches and cementing their place in history. By becoming the first former president to face criminal trial, Trump is instead sitting in court, watching someone else try to define his legacy even as he campaigns for a second term in the Oval Office.

Over four days of testimony this week, former National Enquirer executive David Pecker told the jury not just how deeply involved Trump’s team was in using the supermarket tabloid to fuel his 2016 presidential campaign, but also how celebrities and politicians generally try to buy, trade or bully their way out of scandalous stories.

Prosecutors tried to show that Trump was acutely aware of the machinations being made on his behalf by the tabloid executive and Michael Cohen, Trump’s former lawyer and fixer. After Pecker’s testimony concluded Friday, jurors heard from Trump’s longtime assistant and Cohen’s former banker.

Evidence shows Cohen paid $130,000 in hush money to adult-film actress Stormy Daniels shortly before the 2016 election to buy her silence about an alleged sexual encounter she had with Trump years earlier. Trump is on trial for allegedly falsifying business records related to his reimbursement to Cohen of that payment; prosecutors allege he categorized the payments as a legal fee, rather than a campaign expense, to keep it from public disclosure forms.

The transactional tabloid dynamic was spelled out in raw terms in text messages sent by Dylan Howard, one of Pecker’s top deputies and a former Enquirer editor. The most pointed of those messages were presented to the presiding judge, New York Supreme Court Justice Juan Merchan, but probably won’t be seen by jurors, because Howard is in Australia and for health reasons can’t appear at the trial to testify.

“Information is powerful, and I’m collecting a lot,” said one text from Howard to a close relative in June 2016. At the time, Howard had been assessing the credibility of various people who came forward with scandalous stories about candidate Trump.

“Mind you, in the event that he’s elected, it doesn’t hurt, the favors I have done, provided it’s kept secret,” Howard texted. “At least, if he wins, I’ll be pardoned for electoral fraud.”

For years, Pecker told the jury, he and his friend Trump — then a reality TV star — had a mutually beneficial relationship that involved information-sharing in the celebrity world. When Trump decided to run for president, that relationship kicked into overdrive, as the supermarket gossip sheet published glowing stories about the brash tycoon, and ran many other stories pummeling his political rivals.

Yet the first week of trial testimony showed the arrangement was far from foolproof.

Just four days before the 2016 election, the Wall Street Journal revealed that the Enquirer had secretly paid a Playboy model, Karen McDougal, for the rights to her story about an affair with Trump. The Enquirer then refused to publish the story, a practice known as “catch and kill.”

After the Journal wrote about the arrangement, Trump called Pecker, furious. “How could this happen? I thought you had this under control,” Trump said, according to Pecker. “He was very agitated.”

At the time, Pecker’s company publicly denied buying McDougal’s story to keep her quiet. After being granted immunity from prosecution, however, he testified that was precisely what he’d done.

Cohen promised him he would be reimbursed for paying McDougal, Pecker said, but his lawyers warned him later that such compensation was potentially a crime — and said he may have already broken campaign finance law by paying McDougal.

And so, Pecker testified, he balked at paying again when a lawyer for Daniels came forward to sell her story of a sexual tryst with Trump.

“I am not purchasing this story. I am not going to be involved with a porn star, and I am not a bank,” Pecker said he told Cohen.

Trump ultimately instructed Cohen to pay Daniels $130,000 for her silence, according to evidence from this case and a previous federal investigation. The resulting reimbursements are the reason Trump is now on trial for 34 counts of falsifying business records. He has pleaded not guilty.

The Manhattan district attorney charges that Trump wanted such stories suppressed to aid his presidential campaign, particularly after The Washington Post reported in October 2016 that Trump had bragged on tape about grabbing women by their genitalia. Trump’s defense team has argued that most of what the prosecutors are showing the jury is not criminal conduct, saying that if any crime was committed, it was by Cohen, not Trump.

Prosecutors say Trump’s primary motive in keeping the scandalous stories quiet was to help his campaign, but evidence they elicited from Pecker shows Trump was still trying to keep those secrets after he won the election.

Trump also worried about boxes of documents about him that the Enquirer had acquired over the years, Pecker testified. The executive tried to reassure his friend and Cohen that the boxes of files were harmless — just a collection of old news stories.

Nevertheless, at a meeting at Trump Tower in late 2016, Cohen pressed Pecker to let him go through the boxes. Pecker refused, he said.

At that same meeting, Cohen complained to Pecker that Trump had yet to reimburse him for the money he’d paid to Daniels, and that he also hadn’t received his Christmas bonus from his boss. “He asked me to speak to Donald Trump,” Pecker said in court.

So Pecker urged Trump to pay Cohen his bonus, to which the president-elect replied, “Don’t worry about it, I’ll take care of it.”

Once Trump was president, it became harder to keep his skeletons in the closet, Pecker testified.

Pecker’s deal with McDougal was supposed to keep her quiet, but after the election he amended the deal to allow her to talk to the press — a move that led Trump to call him in a rage.

“You paid her?” Trump asked in astonishment, according to Pecker. “He was very upset. He couldn’t understand why I did it.”

Pecker went even further — he extended McDougal’s contract to do pieces for his various publications, reasoning that keeping her under contract would ensure “she would not go out and give any further interviews or talk to the press or say negative comments.”

The executive testified that he explained his rationale for doing so in a phone call with Trump White House advisers Hope Hicks and Sarah Huckabee Sanders — now the Republican governor of Arkansas. “Both of them said they thought that it was a good idea,” Pecker said.

The efforts of all the president’s subordinates did not assuage Pecker’s growing concern that he had put himself in legal jeopardy by helping Trump in the 2016 election.

In their cross-examination, Trump’s lawyers tried to show the jury that the National Enquirer’s arrangement with Trump was not unique to that political campaign, but part of a long history of buying and sometimes suppressing stories about celebrities.

Pecker testified about a deal he struck with film star Arnold Schwarzenegger before he ran for governor of California, agreeing to shelve embarrassing stories about the actor. In exchange, Schwarzenegger lent his name to Pecker’s workout magazines.

The now-retired CEO said that he used photos of Tiger Woods having an extramarital affair to persuade Woods to give an interview and cover photo for a fitness magazine published by Pecker’s company; and helped suppress negative stories about actor Mark Wahlberg and politician Rahm Emanuel.

But with Trump, the stakes were suddenly much higher, Pecker realized.

He said he received an alarming letter from the Federal Election Commission in early 2018, and immediately called Cohen.

“Why are you worried?” Cohen replied, according to Pecker. “Jeff Sessions is the attorney general, and Donald Trump has him in his pocket.”

Pecker said he was not comforted by that claim, and Trump lawyer Emil Bove tried to use that exchange to show that Cohen — who is expected to testify later in the trial as the prosecution’s star witness — was simply unreliable.

“You were concerned,” Bove asked Pecker, “that Michael Cohen had said something to you that wasn’t true, because President Trump did not have Jeff Sessions in his pocket?”

The lawyer asked Pecker if Cohen was “prone to exaggeration.”

“Yes,” Pecker replied.