Ceasefire brings ‘unusual’ calm for northern Israelis, but fears of Hezbollah threats persist

Silicon Valley had Harris’s back for decades. Will she return the favor?

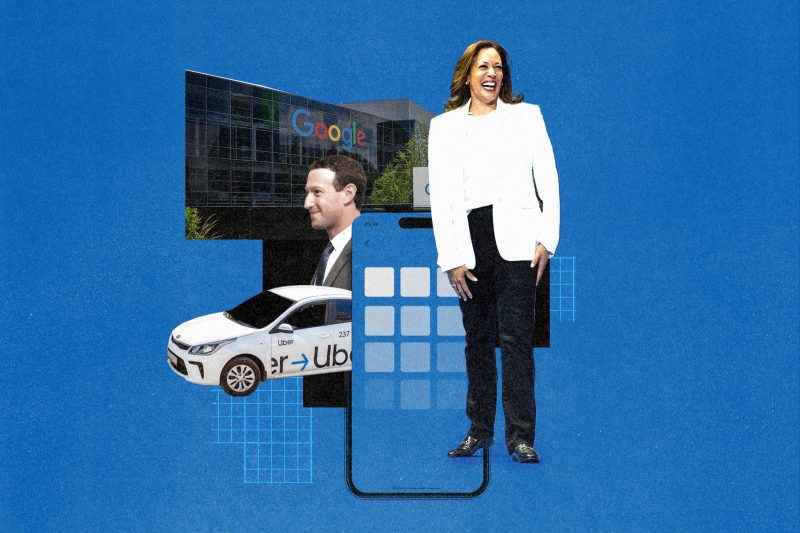

As Vice President Kamala Harris campaigns for the presidency in an election animated by populist energy, some of her chief advisers and donors are positioned against one of the Biden administration’s highest-profile efforts in that vein: reining in Big Tech.

Power players in the tech hothouse of Northern California have long nurtured the political rise of Harris, a native of Oakland, Calif. Donors who made their fortunes in the tech industry helped fuel Harris’s ascendance from San Francisco district attorney to the White House, and her inner circle includes several officials who have worked for Google, Uber and Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg’s philanthropic initiative.

Top industry lobbyists and venture capitalists were in Chicago last month to fete Harris at the Democratic National Convention. They hope their close ties to the nominee might return the industry to its halcyon days during the Obama administration, which embraced innovation in Silicon Valley.

And this week, executives and venture capitalistsare among the hosts of a Silicon Valley Women for Harris-Walz lunch in Atherton, Calif., an enclave for elite tech investors and executives. Tickets are $1,000 and up.

The Harris campaign will have to balance the interests of her longtime supporters in Silicon Valley against resentment of Big Tech’s power across the political spectrum — a sentiment her opponent, former president Donald Trump, is no less keen to harness.

Harris’s Big Tech ties generate anxiety among some liberal Democrats, who say Obama officials’ hands-off approach to regulation let tech companies quash rivals and undermine consumer privacy with impunity. They worry she could abandon the aggressive posture Democrats have taken toward the sector in the nearly eight years since Obama left the White House.

“The fear would be that it would impact her appointments, her policy decisions, her worldview,” said Jeff Hauser, executive director of the Revolving Door Project, a left-leaning advocacy group.

Since President Joe Biden took office, federal enforcers have aggressively gone after giants such as Google, Amazon and Meta over allegations they have run afoul of antitrust laws and illegally harmed consumers, filing a flurry of high-stakes legal challenges. (Amazon founder Jeff Bezos owns The Washington Post.)

Big Tech’s critics, many of them Democrats, have hailed those moves as a sea change for the Justice Department and Federal Trade Commission, which they long accused of a lax approach to the world’s most powerful tech companies.

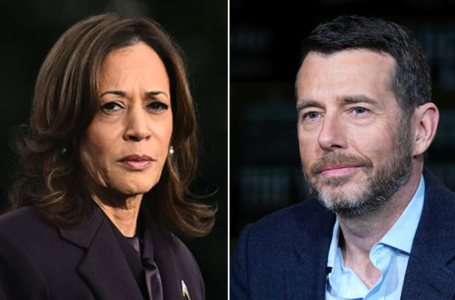

In one telling example of the tensions, top Harris adviser Karen Dunn is leading Google’s defense against the Biden administration in an upcoming antitrust trial, slated to take place a day before next week’s Harris-Trump debate on ABC.

Google goes to federal court on Sept. 9 to fend off a lawsuitfrom Biden’s DOJ seeking to break up the company’s alleged monopoly over its advertising technology, the second antitrust case the federal government is pursuing against the company.

Dunn has emerged as one of Harris’s most influential advisers in the early days of her campaign, helping the nominee prepare for debates and shaping her policy and messaging strategy, as The Washington Post previously reported.

The Trump campaign has criticized Harris’s work with Dunn, calling it a “conflict of interest.”

“Think about how outrageous it is — their administration is suing Google, but Harris is taking political advice from the defendant’s lawyer,” Trump campaign senior adviser Tim Murtaugh told Fox News Digital.

Dunn and the Harris campaign did not respond to requests for comment.

The Harris campaign has also brought on veterans and associates of major Silicon Valley companies, including former Obama campaign manager David Plouffe, who worked as a policy executive for Uber and Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg’s philanthropic venture; former U.S. attorney general Eric Holder, who has conducted audits for Uber and Microsoft; and Tony West, Harris’s brother-in-law, who continues to serve as Uber’s chief legal officer.

Venture capitalists said Harris was speaking their language in her acceptance speech, celebrating her commitment to expand access to capital for “founders” — their preferred term for Silicon Valley entrepreneurs.

Harris would seek to weigh the benefits and risks of artificial intelligence, West said last month in Chicago as part of a DNC panel hosted by tech industry representatives. Tech groups that have raised concerns about the Biden administration’s approach to regulating the technology were reassured by the talk from the campaign’s “informal ambassador to industry,” said Adam Kovacevich, who leads the liberal trade group Chamber of Progress.

“There’s a sense that she will take a fresh look at the issues,” Kovacevich said. “They’re not committing to what’s been done in the past.”

Brian Nelson, a key Harris adviser, told tech officials at the DNC that Harris wants to nurture and protect digital assets, Kovacevich said.The comments signaled that the campaign was trying to regain the support of cryptocurrency leaders who have been flocking to support Trump, amid tensions with the aggressive posture Securities and Exchange Commission Chairman Gary Gensler has taken to regulating digital currencies.

Amazon general counsel David Zapolsky, who leads the company’s efforts to battle antitrust challenges around the world, is a top Harris bundler and attended the convention in Chicago. So did Brad Smith, Microsoft’s president. Amazon is the target of a Federal Trade Commission antitrust suit, and the agency reached a deal that allows it to probe Microsoft’s relationship with OpenAI.

Kovacevich anticipates that a President Harris would focus her tech policy more on the issues she promoted as a senator than on the antitrust concerns of the Biden administration, pointing to her work on online sexual abuse, digital discrimination and privacy.

The debate over Harris’s posture toward the tech sector spilled into public view last month when Reid Hoffman, a major Democratic donor and an ally of the nominee, called on the vice president to fire FTC Chair Lina Khan if elected.

Khan is an icon among liberal Democrats and some conservatives critical of the tech giants, including Trump’s running mate, Ohio Sen. JD Vance. She has emerged as a linchpin of the Biden administration’s battle against corporate concentration, particularly within Silicon Valley. Hoffman, who sits on Microsoft’s board, said Khan was “not helping America” by “waging war” on businesses.

Hoffman’s remarks sparked outrage among the Democratic Party’s liberal flank, promptingconsumer groups to write to Harris, urging her to publicly affirm her commitment to Khan.

“Some billionaires are cranky because they prefer to be able to break laws without accountability, but they don’t get to decide Vice President Harris’s economic agenda,” said Dan Geldon, former chief of staff to Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.).

An unnamed Harris campaign aide told CNN that they have had no discussions about replacing Khan at this time, but Harris has not publicly commented on the issue.

The tech mogul’s remarks could backfire by creating a litmus test for Harris, said Hauser of the Revolving Door Project, because if she replaces Khan, “it’s going to look like she was bought and paid for by Reid Hoffman and a handful of other tech oligarchs.”

As California’s attorney general, Harris pressed tech companies to expand their data privacy protections and worked with digital platforms to curb nonconsensual explicit imagery, sometimes referred to as “revenge porn.” But her public remarks on tech and antitrust have been muddled.

As a presidential candidate in 2020, Harris said regulators “need to seriously take a look” at breaking up Meta, which she likened to an “unregulated” utility, such as gas or electric. But when asked by reporters about antitrust action against the tech giants more broadly, Harris pivoted to the topic of data privacy, which she said would be her “first priority.” While the tech giants are fighting the federal government’s antitrust lawsuits, many have supported calls for federal privacy rules.

Harris has steered a course that both courted and challenged the tech industry throughout her career, especially during her tenure as a U.S. senator from California. Top figures in Silicon Valley, including Hoffman, venture capitalist Ron Conway and Laurene Powell Jobs, the widow of Apple co-founder Steve Jobs, fundraised on her behalf.

“Having been more connected to Silicon Valley for years, I think she has more of a sense of why it is we shape the future through technology,” Hoffman said in an interview with The Post. “And so I think she will be more positive on elements of the technology industry.”

Emily Peterson-Cassin, who tracks corporate power for the liberal advocacy group Demand Progress, said Harris’s donor ties are “absolutely concerning.” But she is optimistic Harris would continue the Biden administration’s tough stance against the tech giants because for Democrats, “the toothpaste is out of the tube,” she said.

There were critical moments during her Senate tenure when she took a tough line against industry. In the 2018 hearings with Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg over the Cambridge Analytica data privacy scandal, she was one of a handful of lawmakers who displayed a strong understanding of social media. She pressed Zuckerberg on whether he and other employees had discussions about disclosing the incident to consumers.

She also championed the Stop Enabling Sex Traffickers Act/Allow States and Victims to Fight Online Sex Trafficking Act, or SESTA-FOSTA, a controversial social media law. The 2018 law chips away at a key tech industry legal shield, making it possible for victims and state attorneys general to file lawsuits against websites that host sex-trafficking ads. Civil liberties advocates and sex workers say the law is too broad.

As vice president, Harris has been the face of many of the administration’s tech policy efforts, including the AI executive order, which requires developers to safety test the next generation of models. Harris traveled to the United Kingdom last year to promote the administration’s concerns about artificial intelligence, focusing on the ways the technology could be used to discriminate. Harris raised concerns about how facial recognition leads to wrongful arrests or how fabricated explicit photos can be used to abuse women.

The administration’s work on artificial intelligence has received a mixed response from Silicon Valley, as venture capitalists and start-ups warn that the order’s requirements to test the next generation of AI systems could create excessive burdens for entrepreneurs.

During her prime-time speech at the DNC, Harris said that she would “make sure that we lead the world into the future” on AI and that the United States, not China, “wins the competition for the 21st century.” The remarks were embraced by tech industry leaders, and lobbyists have expressed hope that a potential Harris administration would consult the industry more than the Biden administration has.

Kovacevich, who previously led Google’s policy team, spoke wistfully of the meetings that the Obama administration held with companies in the wake of the Edward Snowden disclosures, listening to the concerns of industry and law enforcement as Apple and other companies began encrypting users’ messages by default.

“We haven’t seen anything like that in tech policy during the Biden years,” he said. “Tech policy got controlled by folks who stake out a pretty anti-industry position and weren’t interested in a big tent approach.”

Elizabeth Dwoskin contributed to this report.