The lunar far side is wildly different from what we see. Scientists want to know why

When the Chang’e-4 mission landed in the Von Karman crater on January 3, 2019, China became the first and only country to land on the far side of the moon — the side that always faces away from Earth.

Now, China is sending another mission to the far side, and this time, its goal is to return the first samples of the moon’s “hidden side” to Earth.

The Chang’e-6 mission, launched Friday, is set to spend 53 days exploring the South Pole-Aitken basin to study its geology and topography as well as collect samples from different spots across the crater.

The South Pole-Aitken basin is believed to be the largest and oldest crater on the moon, spanning nearly a quarter of the lunar surface with a diameter measuring roughly 1,550 miles (2,500 kilometers). The impact crater is more than 5 miles (8 kilometers) deep.

Scientists hope that returning samples to Earth will help answer enduring questions about the intriguing far side, which hasn’t been studied as deeply as the near side, as well as confirming the moon’s origin.

“The far side of the moon is very different from the near side,” said Li Chunlai, China National Space Administration deputy chief designer. “The far is basically comprised of ancient lunar crust and highlands, so there are a lot of scientific questions to be answered there.”

No real ‘dark side’

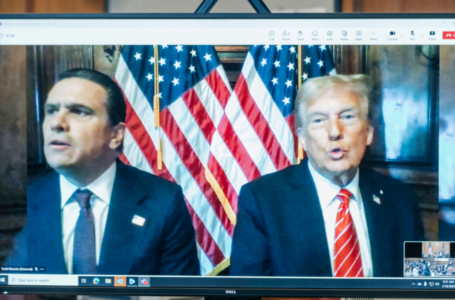

During a NASA budget hearing on April 17, congressman David Trone asked NASA administrator Bill Nelson why China was sending a mission to the “backside” of the moon.

“They are going to have a lander on the far side of the moon, which is the side that’s always in dark,” Nelson responded. “We’re not planning to go there.”

The moon’s hidden side has sometimes been referred to as the “dark side of the moon,” largely in reference to the 1973 Pink Floyd album of the same name.

But the phrase is a bit of a misnomer for a couple of reasons, according to experts.

While the far side of the moon may seem dark from our perspective, it experiences a lunar day and lunar night just like the near side, and receives plenty of illumination. A lunar day lasts just over 29 days, while the lunar night lasts for about two weeks, according to NASA.

The same side always faces Earth because the moon takes the same amount of time to complete an orbit of Earth and rotate around its axis: about 27 days.

Additionally, the far side of the moon has been more difficult to study, which led to the “dark side” nickname and created an air of mystery.

“Humans always want to know what’s on the other side of the mountain and the part that you can’t see, so that’s a kind of psychological motivation,” said Renu Malhotra, the Louise Foucar Marshall Science Research Professor and Regents Professor of Planetary Sciences at the University of Arizona in Tucson. “Of course, we’ve sent space probes that have orbited the moon, and we have images, so in a sense, it’s less mysterious than before.”

Several spacecraft, including NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter that constantly circles and takes images of the lunar surface, have helped to shed light on the moon.

Yutu-2, a lunar rover that Chang’e-4 released in 2019, also explored loose deposits of pulverized rock and dust littering the floor of Von Karman crater, located within the larger South Pole-Aitken basin.

But returning samples to Earth would enable the latest and most sensitive technology to analyze lunar rocks and dust, potentially revealing how the moon came to be and why its far side is so different from the near side.

Far side mysteries

Despite years of orbital data and samples collected during six of the Apollo missions, scientists are still trying to answer key questions about the moon.

“The reason the far side is so compelling is because it is so different than the side of the moon that we see, the near side,” said Noah Petro, NASA project scientist for both the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter and Artemis III, a mission which aims to land humans on the moon for the first time since 1972. “For all of human history, humans have been able to look up and see the same surface, the same side of the moon.”

But in 1959 the Soviet Union sent a probe to fly past the far side of the moon and captured the first images of it for humanity.

“We saw this completely different hemisphere: not covered in large volcanic lava flows, pockmarked with craters, a thicker crust. It just tells a different story than the near side,” Petro said.

Returning samples with robotic missions, and landing humans near the transition between the two lunar regions at the south pole through the Artemis program, “will help tell this more complete story of lunar history that we are lacking in right now,” he said.

Although scientists understand why one side of the moon always faces Earth, they don’t know why that particular side permanently faces our planet. But it could have something to do with the moon being asymmetrical, Malhotra said.

“There is some asymmetry between the side that’s facing us and the other side,” she said. “What exactly caused those asymmetries? What actually are these asymmetries? We have little understanding of that. That’s a huge scientific question.”

Orbital data has also revealed that the near side has a thinner crust and more volcanic deposits, but answers to why that is has eluded researchers, said Brett Denevi, a planetary geologist at the Johns Hopkins University’s Applied Physics Lab.

“It has a different kind of geochemical composition with some weird extra heat-producing elements. There are a ton of models for why the near side is different than the far side, but we don’t have the data yet,” Denevi said. “So going to the far side, getting samples and doing different kinds of geophysical measurements is really important to figuring out this really long, long standing mystery.”

Chang’e-6 is just one mission heading to the moon’s far side as NASA has plans to send robotic missions there as well.

Denevi helped design a mission concept for a lunar rover called Endurance, which will undertake a long drive across the South Pole-Aitken basin to collect data and samples before delivering them to the Artemis landing sites near the lunar south pole. Then, astronauts can study the samples and determine which ones to return to Earth.

Cracking the lunar code

One of the most fundamental questions that scientists have tried to answer is how the moon formed. The prevailing theory is that some kind of object had an impact with Earth early in its history, and a giant chunk that went flying off our planet formed the moon.

Scientists also want to know how the moon’s original crust formed.

Volcanic flows created dark patches on the moon, while the lighter parts of the surface represent the moon’s primordial crust.

“We think at one point the moon was entirely molten, and it was this ocean of magma, and as that solidified, minerals floated to the top of this ocean, and that’s that lighter terrain that we can see today,” Denevi said. “Getting to the really big expanses of pristine terrain on the far side is just one of the goals.”

Meanwhile, the study of impact craters littering the lunar surface provides a history of how things moved around during the solar system’s early days at a critical point when life was starting to form on Earth, Denevi said.

“As impacts were happening on the moon, impacts were happening on the Earth at the same time,” Petro said. “And so whenever we look at these ancient events on the moon, we’re learning a little bit about what’s happening on the Earth as well.”

Visiting the South Pole-Aitken basin could be the start of solving a multitude of lunar mysteries, Malhotra said. While researchers believe they have an idea of when the crater formed, perhaps 4.3 billion to 4.4 billion years ago, collecting rock samples could provide a definitive age.

“Many scientists are sure that if we figured out the age of that depression,” she said, “it’s going to unlock all kinds of mysteries about the history of the moon.”