Western allies rally around Zelensky after Trump spat deepens rift with Europe

The ‘world’s largest’ vacuum to suck climate pollution out of the air just opened. Here’s how it works

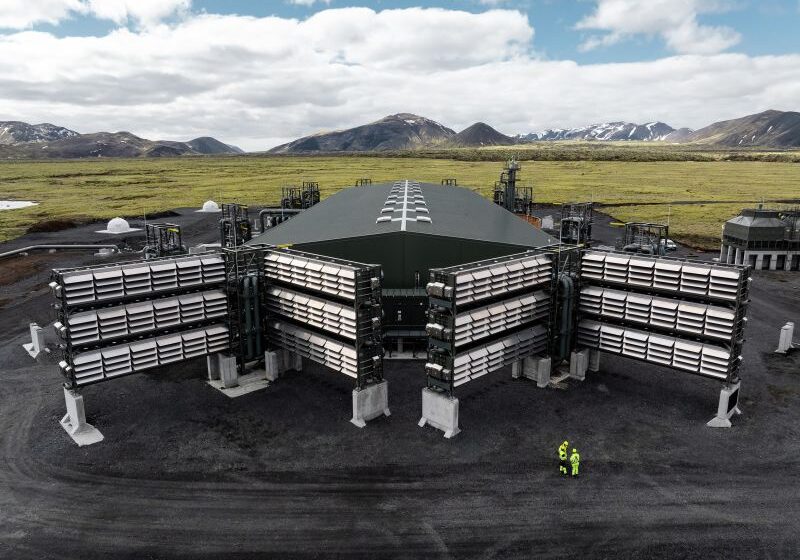

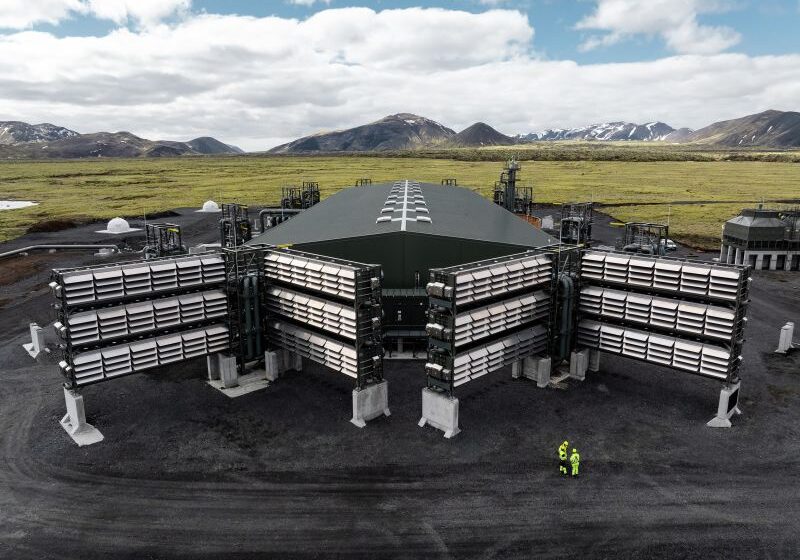

The “world’s largest” plant designed to suck planet-heating pollution out of the atmosphere like a giant vacuum began operating in Iceland on Wednesday.

“Mammoth” is the second commercial direct air capture plant opened by Swiss company Climeworks in the country, and is 10 times bigger than its predecessor, Orca, which started running in 2021.

Direct air capture, or DAC, is a technology designed to suck in air and strip out the carbon using chemicals. The carbon can then be injected deep beneath the ground, reused or transformed into solid products.

Climeworks plans to transport the carbon underground where it will be naturally transformed into stone, locking up the carbon permanently. It is partnering with Icelandic company Carbfix for this so-called sequestration process.

The whole operation will be powered by Iceland’s abundant, clean geothermal energy.

Next-gen climate solutions like DAC are gaining more attention from governments and private industry as humans continue to burn fossil fuels. Concentrations of planet-warming carbon dioxide in the atmosphere reached a record high in 2023.

As the planet continues to heat up — with devastating consequences for humans and nature — many scientists say the world needs to find ways to remove carbon from the atmosphere in addition to rapidly cutting fossil fuels.

But carbon removal technologies such as DAC are still controversial. They have been criticized as expensive, energy-hungry and unproven at scale. Some climate advocates are also concerned they could distract from policies to cut fossil fuels.

This technology “is fraught with uncertainties and ecological risks,” said Lili Fuhr, director of the fossil economy program at the Center for International Environmental Law, speaking about carbon capture generally.

Climeworks started building Mammoth in June 2022, and the company says it is the world’s largest such plant. It has a modular design with space for 72 “collector containers” — the vacuum parts of the machine that capture carbon from the air — which can be stacked on top of each other and moved around easily. There are currently 12 of these in place with more due to be added over the next few months.

Mammoth will be able to pull 36,000 tons of carbon from the atmosphere a year at full capacity, according to Climeworks. That’s equivalent to taking around 7,800 gas-powered cars off the road for a year.

Climeworks did not give an exact cost for each ton of carbon removed, but said it was closer to $1,000 a ton than $100 a ton – the latter of which is widely seen as a key threshold for making the technology affordable and viable.

As the company scales up the size of its plants and bring costs down, the aim is to reach $300 to $350 a ton by 2030 before hitting $100 a ton around 2050, said Jan Wurzbacher, co-founder and co-CEO of Climeworks, on a call with reporters.

The new plant is “an important step in the fight against climate change,” said Stuart Haszeldine, professor of carbon capture and storage at the University of Edinburgh. It will increase the size of equipment to capture carbon pollution.

But, he cautioned, it’s still a tiny fraction of what’s needed.

All the carbon removal equipment in the world is only capable of removing around 0.01 million metric tons of carbon a year, a far cry from the 70 million tons a year needed by 2030 to meet global climate goals, according to the International Energy Agency.

There are already much bigger DAC plants in the works from other companies. Stratos, currently under construction in Texas, for example, is designed to remove 500,000 tons of carbon a year, according to Occidental, the oil company behind the plant.

But there may be a catch. Occidental says the captured carbon will be stored in rock deep underground, but its website also refers to the company’s use of captured carbon in a process called “enhanced oil recovery.” This involves pushing carbon into wells to force out the hard-to-reach remnants of oil — allowing fossil fuel companies to extract even more from aging oil fields.

It’s this kind of process that makes some critics concerned carbon removal technologies could be used to prolong production of fossil fuels.

But for Climeworks, which is not connected to fossil fuel companies, the technology has huge potential, and the company says it has big ambitions.

Jan Wurzbacher, the company’s co-founder and co-CEO, said Mammoth is just the latest stage in Climeworks’ plan to scale up to 1 million tons of carbon removal a year by 2030 and 1 billion tons by 2050.

Plans include potential DAC plants in Kenya and the United States.

This story has been updated with additional information.